Value Mysteries: Picasso Ceramic Owls

In 1946 Picasso was staying near Antibes in the South of France and decorating the walls of what would become the Musée Picasso. A small owl with an injured claw that had been found in a corner ended up living with him and his lover, Francois Gilot. According to Gilot in her book “Life With Picasso” the owl was an ill-tempered creature who smelled awful and ate only mice. The owl would snort at Picasso and bite his fingers; Picasso would reply with a string of obscenities just to show the bird who was the most ill-tempered. Clearly bad manners were the way to Picasso’s heart for not only did he do a number of paintings, drawings and prints of owls, he created numerous ceramics.

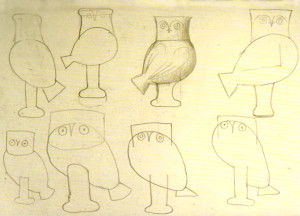

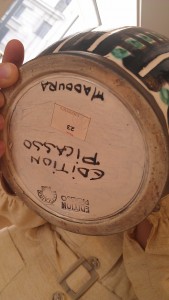

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

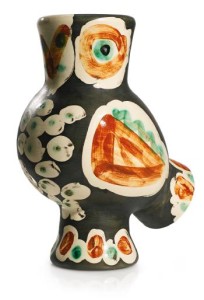

Take a look at five ceramics below that were created at Madoura in 1951. One of them was painted personally by Picasso. The others were painted by the artisans at the pottery after Picasso’s original, what are called “authentic replicas” in the Ramié catalogue raisonne and what are commonly known as Edition Picasso Ceramics. Can you tell which is the one painted by the artist?

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

Of the edition owls above one was of 500 (Picasso ceramics were made in editions of between 25 and 500), so it is not particular rare. The other three were from editions of 300, so already in 1951 there were 1400 owls of this shape flying out of Madoura. You might think that there were really 1401 counting the one that is Picasso’s unique piece, but you would be wrong. In addition to the unique piece (the fourth in the lineup above) which was not made into an edition, there were prototypes for the four other owls that were replicated plus, undoubtedly, other paintings by the artist of this shape. The essence of Picasso’s genius was his being able to tap into a virtually inexhaustible creativity. Once the artisans at the Madoura pottery had created Picasso’s owl shape in ceramic they would have given him some fired pieces which he would have begun decorating. It was not unusual for Picasso to paint a dozen ceramics in a day or more. Altogether he painted over 4000 pieces at Madoura, only 633 of which were made into editions.

There were other owl shapes decorated by Picasso but this, his own, clearly remained one of Picasso’s favorites. A new edition of 300 differently painted owls of this same shape were produced in 1952. In 1958 another edition was created, this one of 200 pieces (the smallest edition of this particular form), not with a white glaze but just the terracotta clay as the mat finish. Ten years later, in 1968, Picasso decorated two more owls in his most complex and colorful design, each editions of 500. A year later, in 1969 just a few years before his death Picasso returned to the shape again with six new pieces — some of his last ceramics, also in large editions. If you add up all the edition owls of this particular shape the total comes to 5,250. Since some shapes were painted just once by Picasso in editions as small as 25, it is safe to say that these owls not only are not rare, they are actually among the most common of the three-dimensional Edition Picasso ceramics.

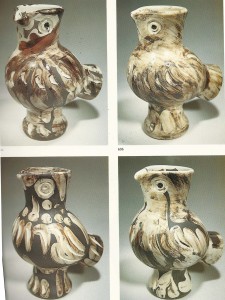

Now consider these four different versions of the form — all from 1969 — and therein lies the mystery:

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

Was that particular version some kind of weird rarity? No, it was simply one of the 500 copies in the edition, which are all supposed to be virtually identical replicas of Picasso’s prototype. Is one of these versions somehow “better” than the others from 1969 (or all the other 5,249 Edition Picasso owls of this shape)? No. In fact these four ceramics are often miscatalogued because they resemble one another so closely and because of their muddy palette they have historically sold for less than some of the more colorful pieces of the same form.

So what gives?

I have spoken about the wild price fluxuations in Picasso Ceramics before, which started with the “Madoura” sale at Christie’s London in June 2012. A lot of it boils down to a thinly traded market, lack of information and clever people trying to exploit one another. The $75,590 owl was Ramié 605, the first owl in the second row, but the huge price wasn’t made at the 2012 Madoura sale. While a copy of Ramié 605 did soar in that sale above its 3000 – 5000 British Pound estimate to achieve 10,625 pounds ($16,554), which was in fact a record high for the ceramic, that price was bested at the Sotheby’s London 2013 sale by almost 400%.

At Sotheby’s 2013 sale several other Picasso ceramics achieved prices higher than pieces from the same editions had at Christie’s historic Madoura sale the previous year. Perhaps the reason was that Sotheby’s, taking a cue from its competitor, had started to specifically target Chinese and Russian buyers. These collectors were already spending big money at the evening sales of Picasso paintings and drawings, the estimates of most of which started at over a million bucks. It was — for them — a new notion that they could pick up Picassos for less than $100,000. So you paid two or three times the estimates – the auction houses often kept estimates low just to get the action going. What bargains!

Of course when you are dealing with a lot of clever people all of whom are trying to outsmart one another reversals aren’t uncommon. There’s probably even Chinese and Russian words equivalent to the one we use in English when there’s a second reversal after the first: the double cross. Lately it’s come to light that some Chinese buyers haven’t paid for items they’ve won at auction. So perhaps once the buyer had a chance to consider things, the record price was something that existed only on paper (and in auction records), not in fact. And maybe underbidders researched the market a bit more thoroughly after the $75,590 record. Six copies of Ramié 605 have traded at auction since 2013 at prices ranging from $15,000 – 20,000 (Ramié 604, 606 and 607 have performed similarly).

Every sale is different, and when you are dealing with thinly traded items anything is possible. You only need two bidders to make an auction. If they both have a lot of money and perhaps not enough information then the sky’s the limit. The owl below, one from an edition of 300, just sold (18 March 2015) at Sotheby’s in London for 37,500 pounds ($55,343) against an estimate of about $4,400 – 7,300. At the same sale four other versions of owls of this shape sold for between $13,000 and $24,000.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

But if everyone gets nervous that the market won’t sustain these prices and a few dozen or hundred (or thousand) owls were to fly out at the same time, look out below.

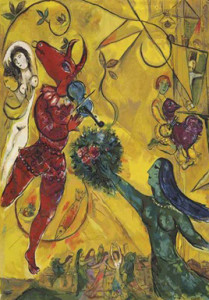

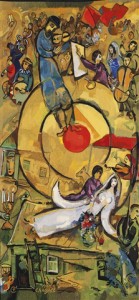

Chagall (and other) Tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince

The name Yvette Cauquil-Prince is virtually synonymous with the term “Marc Chagall tapestry.”

After all, Chagall didn’t spend years mastering the ancient craft of weaving and then sit working at a loom, day after day, for months at a time. Someone else had to do that, and for Chagall — as with artists and their estates including Picasso, Leger, Calder, Kandinsky, Klee, Ernst, de St. Phalle, Brassai and Matta — it was Yvette Cauquil-Prince.

The Belgian-born Cauquil-Prince was Chagall’s best option to continue to explore the medium of tapestry which he had become enamored with after completing a series of tapestries commissioned by the state of Israel. The Chagall tapestries that still decorate the state reception hall of the Knesset had been woven by the Gobelins, the famous French “Manufacture Royale” which was set up by Louis XIV but to this day only takes on gifts of state. Happily Madeline Malraux, the wife of the France’s Cultural Minister Andre Malraux, was acquainted with Yvette Cauquil-Prince and made the introductions.

Chagall was wary at first, demanding that their first effort be destroyed if he didn’t like it. Yvette had a condition of her own — that it be destroyed if SHE found it wanting. Happily both were delighted, and they embarked on a long collaboration and friendship so close that Chagall referred to Yvette as his spiritual daughter. As had Picasso, the artist allowed Yvette to choose the images to be translated into tapestry and didn’t interfere with her interpretive cartooning or weaving as it progressed. After Chagall’s death Yvette remained close to the artist’s family and with their approval continued to create Chagall tapestries, something that Chagall himself had said he wanted. “When I am no longer here, you must continue the work,” he told her. “There will never be a tapestry by Chagall without you.”

Altogether there were only about forty Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince, some of them monumental in size, all of them very small editions or unique (though “editions of one” often provided for an artist proof reserved for the Chagall family). She didn’t actually weave most of these pieces herself. Early in her career Yvette had developed a complex shorthand code by which other weavers in her employ could execute her complex Coptic-influenced interpretative designs — the blueprints that made a Chagall tapestry a Chagall tapestry. By the end of her life in 2005 it could take Yvette up to a year to complete one of these “cartoons” for tapestry.

Cauquil-Prince was recognized by the Louvre as a great artist in her own right, and her Chagall tapestries are widely honored in important private and public collections throughout the world. Because such tapestries are much rarer than Chagall paintings the temptation is to call them “priceless” since they rarely come up for public sale. However, everything has its price and during her lifetime most of Cauquil-Prince’s tapestries were for sale (this was how she made her living). They come back onto the market from time to time.

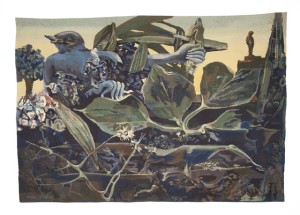

Two of arguably the most beautiful small Chagall tapestries recently appeared at auction. “Liberation” was withdrawn from Sotheby’s New York sale of November 7, 2013. Perhaps the consignor was nervous about it making the presale estimate of $200,000 – $300,000 and sold it privately before the auction. If so, he may have acted too quickly, judging by the very comparable “La Danse” tapestry, which sold at Christie’s London on February 5, 2015, for the equivalent of $306,621 USD. The presale estimate for La Danse was $152,928 – 229,392 USD, reflecting the lower prices that tapestries by other important artists have recently achieved. All tapestries are not created equal, of course. In the last ten years three other small Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince have sold at auction at prices between about $30,000 – $80,000, and one monumental masterpiece brought $385,000 – still the auction record for a Chagall tapestry.

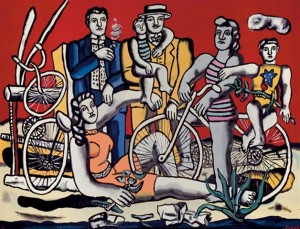

Cauquil-Prince and Chagall were so attuned that Chagall himself declared upon seeing one of her efforts, “This is a real Chagall. It is my hands that did all this.” Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Yvette’s Chagall tapestries sell for higher prices than her interpretations of the works of other artists. However, it would be hard to make a case that Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Leger’s “Les loisirs sur fond rouge” isn’t a spectacular tapestry. Why, then, did it sell at auction for 45% less than the top Chagall? It’s not like Leger is somehow a less important or desirable artist, at least in terms of public sales of paintings. The highest price for a Chagall painting at auction was $14,850,000 versus $39,241,000 for the top Leger lot. If you add up the top ten auction sales for each artist Leger still wins hands down — his top ten sales add up to nearly $176,000,000 versus just $100,000,000 for Chagall.

I often write about value mysteries and in many ways every sale of a work of art qualifies as a mystery. It’s no more strange that Yvette’s Chagall tapestries bring more at auction and than her Legers than the fact that Chagall tapestries are sometimes priced 1000% higher in galleries than they likely can be resold for at auction. However, the real mystery has to do with the tapestries that Yvette Cauquil-Prince created with Max Ernst.

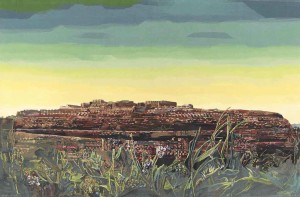

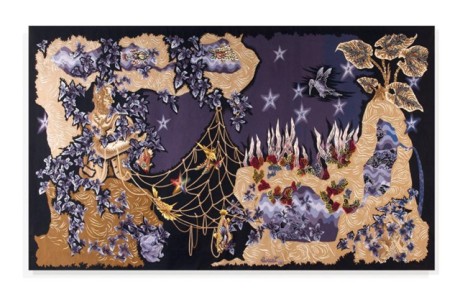

Monumental Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince: “La ville entière” – 111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches

Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976), was a German born Dadaist/Surrealist. His work can be seen numerous important museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, the Hirshhorn, Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and on and on. He sells well at auction. Ernst’s top sale was $16,322,500 vs, $14,850,000 for Chagall, though if you look at the top ten auction prices Chagall thrashes Ernst two to one (why auction prices can be hugely deceptive indicators will be to subject of a future post).

Yvette Cauquil-Prince’s collaboration with Max Ernst actually came about smack in the middle of her triumphant work with Chagall. Chagall called Yvette “my little girl” once too often in front of his jealous wife, Vava, and she banished Cauquil-Prince from working with her husband for a decade. In 1978 Yvette came back to Milwaukee where she had been greeted so warmly upon completion of the Jewish Museum’s Chagall, to present her ten Max Ernst masterpieces,which then toured to Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

Like her Chagall tapestries, Cauquil-Prince’s Max Ernst masterpieces were beautifully interpreted, monumental in scale and woven in very small editions, some of them unique. Because of the difficulty and time-consuming nature of the cartooning and because Cauquil-Prince had to maintain an entire atelier of artisans to weave her pieces on Corsica, it’s likely that the prices for the finished tapestries were comparable to what she had asked for her Chagalls.

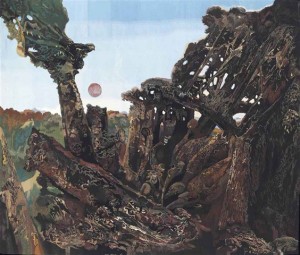

Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” tapestry (76.4 x 106.2 inches) woven by Cauquil-Prince did not fare well at auction

What makes an artist “important” and “desirable” doesn’t necessarily equate to demand across different markets. For collectors of Surrealism, important paintings by Ernst are very desirable. For an American living in the mid-West who is decorating his home, a beautiful tapestry by the famous Chagall is a lot more desirable than some beautifully weird and disturbing tapestry by Max Ernst, who is not exactly a household name in the USA. Still, you’d think that an Yvette Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestry would be worth at least half as much as a Chagall or even a Leger, wouldn’t you?

But you’d be wrong. Not to be cynical, but value doesn’t necessarily have much to do with price, whether at auction or in galleries (it was Oscar Wilde who wrote that “a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing”). The day after the small Chagall “La danse” sold in London for the equivalent of $308,000 against an estimate of 100,000 – 150,000 GBP, a monumental (111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches) Cauquil-Prince Max Ernst tapestry, “La ville entière” was passed a few miles away at Christie’s South Kensington against an estimate of just 10,000 – 15,000 GBP — about $16,000 to $24,000!

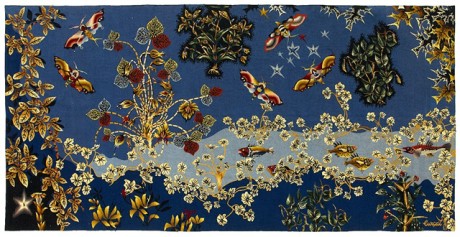

“Totem et Tabou” – Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince measuring a gigantic 163.4 x 194.9 inches

It’s tempting to think that this was some kind of bizarre fluke, but in fact Cauquil-Prince tapestries by Max Ernst have a history of making prices vastly lower than what it would cost to weave them. Christie’s didn’t just pull their estimate out of a hat, it was probably based on Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” which sold at Sotheby’s New York on December 15, 2014 for just $22,500. And it’s not like Sotheby’s was throwing their piece away — they had offered it at an estimate of $25,000 – $35,000 on May 8, 2013 and it had failed to sell (it had brought $36,000 at a 2006 Christie’s sale). “Totem et Tabou,” which is the largest and arguably the most important of Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestries, was passed at Christie’s London on February 7, 2013 with a much more aggressive estimate — 50,000 – 70,000 GBP (78,480 – 109,872 USD).

Bottom line, there just isn’t much demand for Max Ernst tapestries, Yvette’s talent notwithstanding, which to my mind makes them fantastic bargains (provided you like the work of Max Ernst). But auction results can be extremely deceptive indications of prices in the real world. Unless you have a time machine, knowing what was available last year (or yesterday) isn’t worth much. For thinly traded items like tapestries, the “spread” between bid and ask prices can vary wildly. Yes, “La ville entière” may have failed to get a $16,000 bid at Christie’s but it was snapped up within days after the sale. It may very well show up in some dealer’s possession tomorrow with an asking price of hundreds of thousands of dollars, which may be what it really is “worth” but would make it no bargain at all.

Value Mysteries: Jean Lurçat Tapestry Screen

Most dealers and auction houses don’t have a lot of knowledge about tapestries by 20th centuries artists. This makes for a very inefficient, thinly traded market — exactly the type of environment in which smart people can make big profits. Aubussons by Alexander Calder are sometimes still estimated for $2,000 – $3,000 as they were twenty years ago. Though the final hammer prices generally are much higher if word gets out, sometimes no one recognizes what bargains can be had.

Calder didn’t sit down at a loom for months weaving those “Calder” tapestries, of course. He didn’t even see most of them — tapestries are multiples, and Aubussons were generally woven in editions of six with two authorized artist proofs. Long after Calder died, the ateliers were still completing these editions.

It wouldn’t be correct to call tapestry ateliers “factories,” but since they were established by Louis XIV in the 17th Century the “Manufactures Royales” of Aubusson have been businesses that must charge a certain amount per square foot in order to cover salaries, cost of materials, administrative overhead, payment to the artist and profit. Sometimes the marketplace bestows a premium above and beyond what it would cost to replace a tapestry from the weaver. This is especially true for tapestries by Brand Name artists like Picasso, Chagall, Miro, Leger that were woven years ago and the editions are closed out. Here, the line between decorative art and fine art begins to blur and tapestries become rare and collectible artifacts, like first editions by important authors. Tapestries by lesser-knowns, on the other hand, can sometimes be purchased for a fraction of their replacement cost — like used books by forgotten writers.

This tapestry by Saint Saens, an artist influenced by Lurcat, was recently on sale in a retail gallery for less than $10,000

One of the most important names in the tapestry world of the mid-20th century was French artist Jean Lurçat. Lurçat was not a weaver himself but he became a master of the medium and inspired scores of important French artists of the period to work in tapestry, which had been a dying art form.

Between 1900 and 1910 the average annual output of the world-famous Beauvais tapestry workshops was a mere 20 square metres because the weaving costs had risen as high as 38,000 francs per square metre, roughly $60,000 in today’s dollars! Lurçat rescued the Aubusson tapestry ateliers practically single-handedly by simplifying design and production requirements. His innovations brought costs back down to earth and the Aubusson ateliers sprang to life in the 1940s once weaving became profitable again.

Lurçat, however, is not a name known to most Americans. His tapestries and those by important artists who followed his lead are usually sold as decorative pieces with none of the fine art premium that attaches to Calders, Sonia Delaunays and the like. Thus beautiful tapestries by René Perrot, Jean Picart le Doux, Mario Prassinos and Jean Lurçat himself can be found in retail galleries for prices in four figures – far less than the cost of weaving, which it could be argued is their intrinsic value.

Fine art tapestries like other works of art are not commodities. One Miro tapestry is not the same as any other any more than all Picasso paintings are interchangeable in value like pork bellies or ounces of silver. Nor are auction prices reliable indicators of value, though they can provide useful insights.

Take this Lurçat tapestry for instance. “Papillons de Nuits” is a large, fairly typical Lurçat measuring 68.1 x 135.8 inches. It sold under estimate at the Van Ham Kunstauktionen auction in Germany on 1 December 2011 for the equivalent of about $6,000.

“Papillons de Nuits” is a large, fairly typical Lurçat measuring 68.1 x 135.8 inches. It sold under estimate at the Van Ham Kunstauktionen auction in Germany on 1 December 2011 for the equivalent of about $6,000.

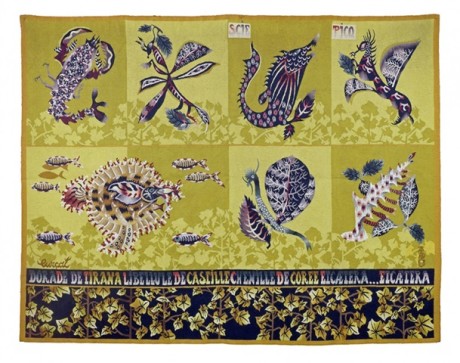

Here’s another, arguably a “better” Lurçat tapestry. Auction records show that “Scie Pick,” 60.2 x 120.5 inches, was passed at Éric Pillon Enchères auction in France of October 26, 2014 against an estimate of 7 – 8,000 Euros (8,868 – 10,135 USD). Another tapestry that looks just like this one but measured only 60.2 x 78.7 inches sold at Drouot-Estimations in Paris on June 13, 2014, for 4,100 EUR (5,544 USD) Hammer. While modern Aubussons are generally limited to a total of eight pieces as indicated above, select tapestries were sometimes “re-editioned” in different sizes — a way of capitalizing on the more successful images (and making them not quite as “rare” as edition sizes would seem to indicate).

Here’s another, arguably a “better” Lurçat tapestry. Auction records show that “Scie Pick,” 60.2 x 120.5 inches, was passed at Éric Pillon Enchères auction in France of October 26, 2014 against an estimate of 7 – 8,000 Euros (8,868 – 10,135 USD). Another tapestry that looks just like this one but measured only 60.2 x 78.7 inches sold at Drouot-Estimations in Paris on June 13, 2014, for 4,100 EUR (5,544 USD) Hammer. While modern Aubussons are generally limited to a total of eight pieces as indicated above, select tapestries were sometimes “re-editioned” in different sizes — a way of capitalizing on the more successful images (and making them not quite as “rare” as edition sizes would seem to indicate).

Auction prices can be greatly misleading, and it would be foolish to believe that somehow $5,000 or $6,000 “should” be the price of a Lurçat tapestry. In fact they have sold at much higher prices both at auction and in galleries.

Jean Lurçat’s

“Chasse et pêche” measuring 81 x 140 inches sold at a French auction in 2011 for the equivalent of $44,000 – probably less than it would cost to have a similar piece woven today. In a retail gallery it would be priced much higher.

It’s not likely that most people looking for a large artwork to place on a wall in their home would have been considering tapestries when the above pieces sold inexpensively at auction, nor is it likely that Americans would have even found these particularly obscure sales. Even if you have a time machine, it’s not like you can actually buy these tapestries for the recorded auction prices — you will simply be able to make the next bid. Unless the actual buyer then just gives up, the price could go much higher. In fact many Lurçats have sold for much more at auction and in galleries, which is where most tapestries are sold to end users. Retail buyers generally need someone to explain why a tapestry might be better for them than a painting and time to consider the type of image and the size that might work in their home.

But the fact is that Lurçat is not a “hot” artist. There is not much demand for tapestries in general, let alone for tapestries by Lurçat. This is why most sell — even in retail galleries — for less than it would cost to weave them. To some people that would indicate “value” and “bargain.” Others would probably be thinking “White Elephant.”

So what would you call this Lurçat tapestry screen that I saw recently in the booth of a fashionable French gallery at a high end art and antiques fair in New York?

While it appears at first to be an eight panel screen, closer examination reveals that it is actual four two-piece panels, making it much easier to transport and set up. Actually it’s a pretty ingenious thing to do with very large horizontal tapestries like the ones illustrated above, which generally are harder to sell than smaller pieces which can be more easily placed. In fact this screen is 90.5 x 220.5 inches — over 18 feet across!

While it appears at first to be an eight panel screen, closer examination reveals that it is actual four two-piece panels, making it much easier to transport and set up. Actually it’s a pretty ingenious thing to do with very large horizontal tapestries like the ones illustrated above, which generally are harder to sell than smaller pieces which can be more easily placed. In fact this screen is 90.5 x 220.5 inches — over 18 feet across!

Such a huge tapestry was probably commissioned for a specific space — this is not the type of thing you weave on spec and then hope to find someone with a gigantic room they want to hang a tapestry in. Perhaps when the original owner died somebody needed to be creative in order to sell this gigantic thing and had it mounted. However, the woman in the booth at the fair explained imperious tone that this was designed by Lurçat specifically to be a screen, in fact it was the only such screen he ever created.

When I asked if there was some documentation for this claim I was given the look that dealers reserve for Martians and other ignoramuses. Obviously if I were one of those crazy Americans obsessed with minutia, I wasn’t a likely prospect to buy anything. Especially a rare tapestry screen like this one priced at $160,000!

Well, maybe the story was true, maybe it wasn’t. However, the bottom line of value is always determined by supply and demand. There were hundreds, possibly thousands of Lurçat tapestries woven; few people are looking specifically for this type of thing, hence prices are often below intrinsic cost. However, this smart French dealer is trying to change the equation. He’s saying that the supply is not thousands but — if you believe the story — only one. And while demand by knowledgeable buyers of tapestries for an impossibly large Lurçat is minimal, a lot of rich people on Park Avenue with big walls and collectors of trendy Mid-Century Modernism shop at prestigious art and design fairs. They’ve probably never seen anything like this (partly because they don’t shop in those places where Lurçat tapestries can be purchased for less than $10,000).

Whether the screen sold for anywhere near the asking price or at all, I do not know. What I do know is that somebody bought this very same Lurçat at Sotheby’s Paris on November 26, 2013 for a little more than $20,000. The Value Mystery is whether the French dealer will be able to sell it, how long will it take, and how much will it finally bring? At full price somebody stands to make a 700% profit in a year, but that $160,000 probably is not a great deal higher than it would cost to weave such a tapestry today.

So what about this other Lurçat tapestry screen measuring a much more practical 89 x 32 inches that sold at the Leland Little Auction & Estate Sale of March 17, 2012, for a total price of $2,000? What kind of value should be placed on it?

So what about this other Lurçat tapestry screen measuring a much more practical 89 x 32 inches that sold at the Leland Little Auction & Estate Sale of March 17, 2012, for a total price of $2,000? What kind of value should be placed on it?

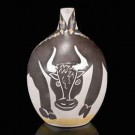

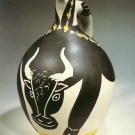

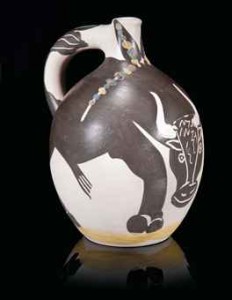

Value Mysteries: Picasso’s Runaway Bull Returns

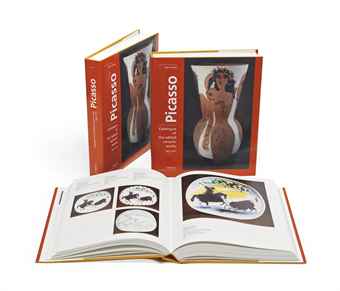

In my previous post I discussed the Case of the Picasso Ceramic Bull, “Taureau” as he is called in Alain Ramié’s definitive ““Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works, 1947 – 1971.” Alain Ramié is the son of the Georges and Suzanne Ramié who created Picasso’s edition ceramics at the Madoura pottery.

The first of these Taureaus (AR 255 as it is identified in the catalogue raisonne) to sell at auction brought $87,000 in 1990. For the next two decades, however, at least eighteen other bulls from the edition of 100 sold (or were passed) at auction for prices averaging in the $20,000s. As late as April 2010 one sold at Christie’s in New York for $27,500. In October that same year another brought $25,000 at Sotheby’s New York. But something very strange happened at the next sale of AR 255, which took place at Christie’s South Kensington on June 25, 2012. The price was 97,250 British pounds — $151,263!

The first of these Taureaus (AR 255 as it is identified in the catalogue raisonne) to sell at auction brought $87,000 in 1990. For the next two decades, however, at least eighteen other bulls from the edition of 100 sold (or were passed) at auction for prices averaging in the $20,000s. As late as April 2010 one sold at Christie’s in New York for $27,500. In October that same year another brought $25,000 at Sotheby’s New York. But something very strange happened at the next sale of AR 255, which took place at Christie’s South Kensington on June 25, 2012. The price was 97,250 British pounds — $151,263!

What the hell happened in the intervening year and half that drove the price of Picasso’s ceramic Taureau up 500%?

To answer that question it is helpful to go back to last post where I discussed the factors that drove the price of the first Bull into record territory:

“Market inefficiency drives price volatility and, as with many markets, there are three factors that create inefficiency for Picasso ceramics: lack of knowledge, thin trading and what some people might call manipulation but which in reality is simply the interaction of small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.”

Did any of these three factors exist after twenty years of stable prices for this ceramic? You’d think all the angles had been covered by now, and everybody knew all there was to be known, wouldn’t you?

Did any of these three factors exist after twenty years of stable prices for this ceramic? You’d think all the angles had been covered by now, and everybody knew all there was to be known, wouldn’t you?

But in fact all of these conditions still existed on June 25, 2012 when “The Madoura Collection” went up for sale in South Kensington. Parsing the facts, however, is difficult because in the art market — as in quantum physics — the facts change depending on how they are observed and by whom.

Let’s not call it manipulation because Christie’s in fact was smarter than everyone else when they packaged hundreds of ceramics that had been consigned by Alain Ramié into a hugely publicized, once-in-a-lifetime, sale-of-the-century type affair on June 25, 2012.

Looking like it had been made yesterday, this Grand Vase was the Madoura Sale’s top lot, selling for the equivalent of $1,146,143

Christie’s sale rooms in South Kensington were a perfect venue — one of the priciest neighborhoods in the world and the kind of place where the street traffic is comprised of billionaires. Right there in the window were scads of these charming, wacky Picasso pots and plates, which probably a lot of billionaires and their sisters and their cousins and their aunts had never seen before. These are the sort of folks who usually only bother with the big evening sales where even “restaurant Picassos” start at a couple million bucks. (“You know, Restaurant Picassos,” as Steve Wynn once educated me. “They’re not good enough for my museum so I put them in the restaurant.”) Here was an opportunity to pick up a genuine Picasso with the best provenance imaginable in such pristine condition that it looked like it had been made yesterday for estimates that began at a mere 1,000 pounds or even less. Stocking stuffers!

People who attended the previews reported that these were the archive copies of the Madoura pottery, the “bon à tirer” pieces, the very prototypes approved by Picasso so that editions could be recreated and sold inexpensively (originally) to the tourists. Strangely the Christie’s catalogue itself did not mention any of this, other than to identify the sale as “the Madoura Collection” and specify the edition size. In other words you might have bought the story but as in any auction you weren’t buying actual documentation beyond what was printed in the lot description.  Many of the ceramics were marked “Exemplaire Editeur,” which led to a lot of grumbling among cynics and old-time dealers who had been buying ceramics directly from Madoura — in some cases since the 1960s — and had never heard of anything marked “Exemplaire Editeur.” Nothing about Exemplaire Editeurs had been mentioned in the catalogue raisonne. How many of these things were there and when were they really made?

Many of the ceramics were marked “Exemplaire Editeur,” which led to a lot of grumbling among cynics and old-time dealers who had been buying ceramics directly from Madoura — in some cases since the 1960s — and had never heard of anything marked “Exemplaire Editeur.” Nothing about Exemplaire Editeurs had been mentioned in the catalogue raisonne. How many of these things were there and when were they really made?

The same people also complained that the person who Christie’s (and Sotheby’s) trusted to judge the authenticity of Picasso ceramics was the same person who consigned the pieces, a rather serious conflict of interest! No matter. It wasn’t the cynics who were going to buy at the Madoura sale, any more than they would have shelled out a thousand dollars for a $50 cookie jar at the Andy Warhol Estate sale or God only knows how much for Jackie Kennedy’s dental floss. The once-in-a-lifetime Madoura sale was geared toward once-in-a-lifetime buyers — this was their last chance to buy directly from the source. And buy they did. The two-day Madoura Collection sale was a huge success, taking in over £8,000,000 ($12,500,000), four times its total presale estimate, and was 100 percent sold by lot and by value.

It is interesting to note that not all of the ceramics in the Madoura sale were Exemplaires Editeur. Some were ordinary numbered and unnumbered production pieces. Others bore strange numbering like 113/157/200. A “Grand Vase” that sold for £265,250 was marked H.C 1/3. H.C. is an abbreviation for Hors Commerce, which basically meant not for sale. There is no mention of H.C. Picasso ceramics in the catalogue raisonne. These ceramics skyrocketed past their estimates like everything else.

When the purchasers go to sell their copies, will the market reward them for coming from the historic Madoura Sale (presuming the buyers have kept their receipts)? Or will they find their ceramics valued just like all the hundreds of identical others in the editions?

When the purchasers go to sell their copies, will the market reward them for coming from the historic Madoura Sale (presuming the buyers have kept their receipts)? Or will they find their ceramics valued just like all the hundreds of identical others in the editions?

And what about Taureau, AR 255, Picasso’s Bull that ran away in value? Will it continue to bring a huge premium over its bovine brethren?

In fact a year later the price of Taureau was down by more than half, an example from the edition selling at Christie’s New York for $68,750. A few months later Christie’s South Kensington did better, getting the equivalent of over $91,000 for one (rumor has it that they specifically targeted Chinese internet buyers who had no idea that genuine Picassos could be had so cheap). Not bad, but of course not in the same league as that Exemplaire Editeur Taureau that garnered $151,263 at the Madoura sale. How much, I wonder, is that once-in-a-lifetime ceramic worth today?

In fact, buried at the bottom of the definitions and abbreviations page of Alain Ramié’s catalogue raisonne is the note that there are three “publisher’s copies” for each piece. So perhaps there will be two more “once-in-a-lifetime” Madoura sales in the future. But an Exemplaire Editeur Taureau may not be in both: I appraised one purchased directly from Madoura in 2005.

Value Mysteries: The Case of the Runaway Picasso Bull

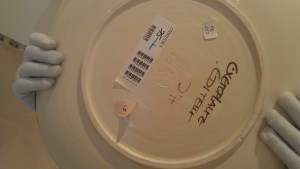

Working at the Madoura Pottery in the village of Vallauris in the South of France Pablo Picasso hand-decorated over four thousand ceramics between 1947 and his death in 1973. Over 600 of these were selected to be replicated in editions of 25 to 500 by the artisans at the Pottery and sold inexpensively to the tourists. For the last thirty some years they have been bought and sold at auctions and in galleries around the world. Studying these sales can bring fascinating insights into markets in general and the art world in particular.

Market inefficiency drives price volatility and, as with many markets, there are three factors that create inefficiency for Picasso ceramics: lack of knowledge, thin trading and what some people might call manipulation but which in reality is simply the interaction of small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

Ironically, until recently the highest prices for Edition Picasso ceramics were achieved in the 1980s when the Japanese appeared to be on the verge of taking over the world. At the beginning of the decade it was the Japanese who knew something that everyone else didn’t: that ceramics had always been the true fine art in Japan, a culture where oil painting had not traditionally existed. Tremendous wealth was flowing toward Japan and the Japanese wanted to experience the best that the Old World had to offer in luxury products, fashion, food, entertainment and of course art. Well-heeled Japanese who weren’t rich enough to buy important European paintings could pay twice the asking price for a Picasso plate and feel they had gotten a tremendous bargain. Prices soared. By mid-decade Sotheby’s and Christie’s, which for years had turned up their noses at Picasso ceramics as mere tourist curiosities, began to include them in sales. Prices went even higher. Yet few people understood what these items were, where they were made, who made them and how many were created.

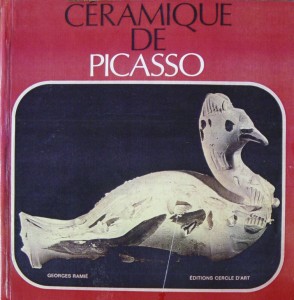

Because Picasso ceramics were low-priced vacation “souvenirs,” there was little published information available. Not even the book written by the owner of the Madoura Pottery, Georges Ramié (which was only available in French for several years), offered much hard data. Georges Ramié’s “Ceramiques de Picasso” pictured various of Picasso’s unique prototypes without explaining that there were perhaps hundreds of “authentic replicas” of the pictured pieces. This inevitably led to confusion among buyers and sellers alike as to whether ceramics were originals or edition pieces (in fact the vast majority of ceramics decorated personally by Picasso were never for sale and are still owned by members of the Picasso family and museums).

When this Bull appeared at auction it was probably the first time that anyone in the prestigious sale rooms had ever seen anything like it. But novelty wasn’t the only reason that this Bull sold at Sotheby’s London on October 18, 1990 for 44,000 British Pounds, then the equivalent of $87, 824. Knowing that the Japanese were voraciously pursuing Picassos a dealer may have made the top bid for this ceramic, figuring he could sell it to some rich fool in Tokyo. It only takes two bidders to achieve a record auction price and unknowingly the buyer might have been bidding against the one Japanese collector who would have paid a top retail price for this ceramic. Or perhaps there was a second dealer who thought he too was smarter than everyone else, was willing to take risks and believed there was no limit to the Japanese mania for Picasso ceramics. We’ll never know. What we do know is  that one month later, on November 19, 1990 another Picasso ceramic Bull just like the first sold for $39,600 at Christie’s in New York City.

that one month later, on November 19, 1990 another Picasso ceramic Bull just like the first sold for $39,600 at Christie’s in New York City.

A 55% decline in one month would be considered a crash in any market (the great Stock Market Crash in 1929 was a mere 12.82%). Certainly one factor in the price decline was lack of information, but that was about to change — sort of. In 1989 Alain Ramié, the son of Georges, published “Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works.” I say “sort” of because both Georges and Alain Ramié’s books were popularly referred to as the Ramié Catalogue and to this day they are confused with one another. Each gave numbers to the pictures of Ceramics they included but the only Ramié numbers that now mean anything to dealers, collectors and auction houses are the numbers from Alain Ramié’s book. It is an authoritative catalogue raisonne compiled from the records of the Madoura Pottery and includes definitive measurements, descriptions, edition sizes and pictures. Sometimes (but not always) these numbers are referred to as AR numbers. Thus the professional shorthand for this Bull is R 255 or Ramié 255 or AR 255.

Around the time of the record 1990 sale anyone with access to the Alain Ramié catalogue would have known that the Bull was one of an edition of 100. In fact that’s how Sotheby’s identified it in the auction catalogue, but clearly the bidders weren’t aware of or discounted this information. In fact edition size is a problematic fact. After all, it’s not like there are actually 100 of these ceramics available for sale at the time of any given auction — there is only one. It might be years or even decades before another appears for sale (then again, it could be weeks). Of course there’s nothing like a record sale to alert all of the other owners of a similar item that now may be a good time to sell — often gaggles of similar pieces suddenly appear out of the woodwork at the next sale once a record has been achieved.

how Sotheby’s identified it in the auction catalogue, but clearly the bidders weren’t aware of or discounted this information. In fact edition size is a problematic fact. After all, it’s not like there are actually 100 of these ceramics available for sale at the time of any given auction — there is only one. It might be years or even decades before another appears for sale (then again, it could be weeks). Of course there’s nothing like a record sale to alert all of the other owners of a similar item that now may be a good time to sell — often gaggles of similar pieces suddenly appear out of the woodwork at the next sale once a record has been achieved.

In the stock market there are millions of shares, and the “spread” between the bid and ask prices can be a fraction of a penny. However, for thinly traded items the spread can be enormous. In hot markets this may work to the seller’s advantage: you might have multiple bids on your million dollar Miami Beach condo in 2007. But if the buyers suddenly disappear like they did for Florida real estate in 2009 you may have one offer and it might be for $400,000. This is what happened to the artworld when the Japanese “Bubble Economy” burst. The music suddenly stopped, the Japanese buyers disappeared, seemingly from one day to the next. Just as with people holding Collateralized Mortgage Obligations in October 2008, anybody who hadn’t already found a “greater fool” to sell to was stuck.

If the underbidder felt bad about losing the Bull at Sotheby’s October 1990 sale, he probably felt a lot better after the Christie’s sale the next month. And the buyer who bought the Ramié 255 Bull at a 55% discount (perhaps the same underbidder?) may have thought he was a genius. He would have been mistaken. The following year, on November 4, 1991, a Bull sold for $24,200, again at Christie’s in New York, nearly 40% less than the “bargain” November 1990 price. (Of course any dealer with a Bull of his own had immediately raised the price of the one in his shop to at least the $87,000 after the October 1990 Christie’s sale and many never adjusted their price downward — but this will be another post.)

Nearly twenty years later the Picasso Edition Ceramic Bull AR 255 was still changing hands at about the same price it brought in 1991 (one sold at Sotheby’s New York on October 29, 2010 for $25,000).

You would think that the market is more efficient these days, wouldn’t you? That lack of information is no longer an issue, that edition sizes have been discounted in the prices, and that mature markets like the long-standing one for Picasso ceramics can’t suffer from small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

You would think that the market is more efficient these days, wouldn’t you? That lack of information is no longer an issue, that edition sizes have been discounted in the prices, and that mature markets like the long-standing one for Picasso ceramics can’t suffer from small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.

How then would you explain the Edition Picasso Ceramic Bull that sold on June 25, 2012, just a year and half after a two-decade string of $25,000 – 35,000 sales, for 97,250 British pounds at Christie’s South Kensington, then equal to $151,263?

I’ll try in my next post.

A Conspiracy of Paper

“A Conspiracy of Paper” was mystery writer David Liss’s first novel, published in February 2000. It’s a meticulously researched story of a Jewish boxer in 18th century England who gets involved in stock market manipulations that have eerie parallels to what goes on in financial markets today.

I bought the book when it first came out because I like the period and am interested in the stock market. Also, I must confess, I was jealous. I was an active mystery writer at that time, and frankly I wanted to know what kind of book a big-deal publisher like Random House would throw its weight behind. “A Conspiracy of Paper” came out the gate with a bang-up review in the Sunday New York Times and ended with an Edgar for Best First Mystery Novel of the year. And in fact it was a great read. At least I consoled myself with the thought that I  had purchased a first edition (I felt it only right to buy fellow writer’s books, hoping that some of them might follow the golden rule, too), and it would probably be worth something one day. Back then first novels by writers who were hot brought big prices at the many bookstores across America that specialized in mysteries. A mystery writer friend of mine who was practically living out of her car was kicking herself for not having saved a few copies of her first novel which was then selling for almost as much as the advances I received from St. Martins Press.

had purchased a first edition (I felt it only right to buy fellow writer’s books, hoping that some of them might follow the golden rule, too), and it would probably be worth something one day. Back then first novels by writers who were hot brought big prices at the many bookstores across America that specialized in mysteries. A mystery writer friend of mine who was practically living out of her car was kicking herself for not having saved a few copies of her first novel which was then selling for almost as much as the advances I received from St. Martins Press.

Today, sadly, there are few if any mystery bookstores left, and if you want to read “A Conspiracy of Paper” you can for $9.99 download it for your Kindle. But we’re remodeling our small New York apartment and there simply isn’t room for all the books so today was the day that I decided to cash in on my investment.

In terms of dollars, selling your books is orders of magnitude less consequential than selling your stocks or your art, but in certain ways it can offer clearer insight into how markets function. Bookstores and book dealers don’t just make the market for books — they physically OWN the market. Unless you own a bookstore, too, books are virtually unsellable except maybe through Ebay (which for low priced items is more trouble than it’s worth). Luckily in New York City we have the Strand, one of the largest independent bookstores in the world and one that actively purchases books — but strictly on their terms. The Strand is not only prepared but happy to deal with walk-in sellers. Computers allow them to scan the bar code and have instant information about how much they can offer.

Some people might characterize these offers as a conspiracies not of paper, but of spare change. Therein lies the reality of all markets: it is demand that drives prices, not supply. You may have an extremely rare volume, but it doesn’t matter what you think it is “worth.” Yours may be from a tiny edition. The author might be loved by critics and readers alike. You may have seen one in a store for a hundred dollars. None of this matters. The only real question is how many people would buy it if they knew that yours was available for sale? (Perhaps that’s why signed first editions of my mysteries, tiny editions all, linger on Abebooks.com for less than $30.00, but that’s another story.)

If you take your books to the Strand, they won’t even consider anything that isn’t in perfect condition because you probably purchased your books from Barnes and Noble, not Sotheby’s. You don’t have a book collection, you have a lot of used books — and as with used cars or used furniture, a used book has to look pretty good if it’s going to appeal to anybody. The Strand will save you the trouble of shlepping home less than perfect editions — they put them out on the $1 sale tables — but they won’t give you a nickel for a wheelbarrow of them. For books in pristine condition they might pay a few dollars, take it or leave it. Even very nice art books will probably bring less than $10. Again, if you don’t like their offer you can go become a book dealer yourself. Go ahead, try your to sell first edition John Updike on Ebay. According to the Strand, nobody really collects Updike, regardless of how great the New York Times thought his books were — and the press runs were huge so there’s plenty of supply out there. There’s no demand for John Grisham, or most other best-selling authors, either — and the supply is even larger for this stuff. You may point out that booksellers on Abebooks are asking hundreds of dollars for that rare classic the Strand is offering you two bucks for. They will point out that they’ve had six upstairs since 1992, none have ever sold. Why do they need to buy another one at any price?

And those fancy art books? A gallery owner friend of mine bought a few boxes of Chagall catalogues raisonnes when they came out decades ago. Art dealers and appraisers need to buy these essential references so there is a legitimate demand — you can find them one Abebooks for hundreds of dollars. But how many art appraisers are there and how many don’t already have copies? Thirty bucks was all the Strand would offer, and they certainly didn’t want all twenty, the most they might take was one or two. It could take years to sell them and, after all, they already had a few copies.

And David Liss? If you go to Advanced Book Exchange you can find a signed first edition of “A Conspiracy of Paper” in perfect condition for $120. Unfortunately you can also find perfect signed firsts for $10, to say nothing of all the unsigned copies. Publishers support their books to make sales in the primary market, not the secondary one. Random House sent out hundreds of promotional copies, had a national advertising campaign so they could sell enough of that big first printing of Liss’s first novel to make a profit. Everybody thought the author was going somewhere, so plenty of people saved their copies. The Strand already has a ton of them and hasn’t sold one for years. That’s why they didn’t want mine at any price. And I wasn’t going to shlep it home and wait for collecting first mystery novels to come back into fashion.

It will probably be on the $1 table for a long time to come.