All Calder Tapestries Are Not Created Equal

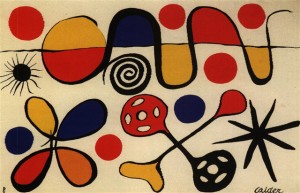

Alexander Calder (American, 1898 – 1976) may be best known for his stabliles and hanging mobiles but he also worked in almost every medium imaginable — paintings, prints, jewelry, stage sets and wire sculpture — he even decorated airplanes.

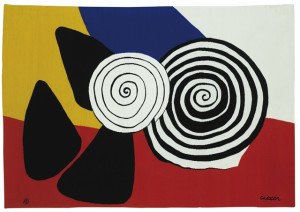

Beginning in the 1960s Calder aligned himself with important French weavers, most notably Pinton, which recreated his designs in fine art tapestry. Calder’s work was graphic, simple and perfectly suited to the medium, which made it both highly desirable to art buyers and profitable for the tapestry ateliers. Ultimately there were more tapestries by Calder than by nearly any other well-known artist.

“Les Passoires,” the most expensive Calder recorded at auction sold in 2007 for the equivalent of $77,810 without premium. Six years later in 2013 another copy from the edition sold for $5,000 less — premium included.

Some dealers now are asking over a hundred thousand dollars for Calder Aubusson tapestries, though they certainly can be found for less — not just because of the number available (there were over 60 different Calder designs made into small-edition Aubussons), but because there is a lot of confusion in the market place about this lesser-known medium. These days people use the word “tapestry” to refer to any textile that can be hung on a wall for decoration. You can take a blanket off your bed, tack it up over the window and call it a tapestry — no Vocabulary Police will arrive to arrest you. Consequently some types of Calder “tapestries” are worth a lot more than others.

There are basically five types of what people call “Calder tapestries”: 1) Aubussons; 2) Bicentennial Aubussons; 3) Natural Fiber Wall Hangings; 4) Pile rugs and carpets (tapis); and 5) Problematic Items

CALDER AUBUSSON TAPESTRIES

The tradition of weaving textiles goes back to ancient times. Horizontal stands of wool (or other material) called weft threads are passed between vertical warp strands that are affixed to a wooden frame called a “loom.” Colors are changed to create patterns or images. The resulting textile are called tapestries. The “Sun King” of France, Louis XIV, set up Manufactures Royales like the Gobelins to weave tapestries in this tradition for his palace at Versailles, and French tapestries woven in this manner are generically called “Aubussons.” Aubusson is actually a town in central France, which Louis declared a “Manufacture Royale” in 1665. Its output, and the output of ateliers in its sister city of Felletin (declared a Manufacture Royale in 1689) has always been commercially available and tightly controlled for quality.

A smaller ( 66 x 49 inches) and less colorful Calder Aubusson sold in November 2013 at a more obscure French auction for a hammer price of about $4,000.

It can take a skilled weaver a month to create a square meter of a fine Aubusson, so these French textiles — handwoven in the most famous tapestry ateliers in the world — have always had intrinsic value. Supply and demand has resulted in people willing to a premium above the weaving costs for images by important artists.

Some of the differences in pricing of Calder Aubussons has to do with basic considerations such as size. Large tapestries tend to cost more than small ones since their original retail cost was higher because they took longer to weave. Sometimes, however, very large tapestries can be difficult to resell because there are fewer potential buyers with giant walls. This is one factor that makes auction prices for tapestries so deceptive. There is very definitely a “sweet spot” in terms of size — if it’s too big or too small fewer people will bid.

Quality is also a factor. Buyers are sometimes more attracted to busier, more colorful images, but sometimes art can be too busy and too colorful. Or too quiet and not colorful enough. It’s a matter of taste and trends. Calder is much more popular now than he was twenty five years ago and Calder Aubussons are very much in demand.

CALDER BICENTENNIAL AUBUSSONS

1976 was the two hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Bi-Centennial. As part of the celebration a special series of 6 different Calder Aubussons was commissioned. Aubusson tapestries are limited in France to editions of no more than 6 with two authorized proofs — a maximum total of eight pieces. What made the Calder Bicentennial tapestries special is that the French government in the spirit of celebration allowed 200 sets to be woven. It was a magnanimous gesture — and an optimistic one.

eight pieces. What made the Calder Bicentennial tapestries special is that the French government in the spirit of celebration allowed 200 sets to be woven. It was a magnanimous gesture — and an optimistic one.

Only about 45 sets were actually ever made, which leads to confusion about supply in both directions. People have assumed that since the Bicentennial tapestries are Aubussons they must be editions of only six. Others assume that there were actually 200 tapestries made of each design. Whether 8, 45 or 200 were made, demand is actually more important in the pricing of tapestries (and most art) than supply. The Bi-Centennial Calder Aubussons are physically smaller and the designs generally less complex and graphically interesting than the most desirable Aubussons, so there is less demand and prices usually are significantly lower.

Bottom line: Depending upon the asking price, Calder Bicentennial tapestries may or may not be the bargains they seem to be.

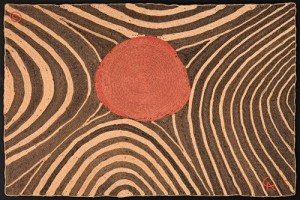

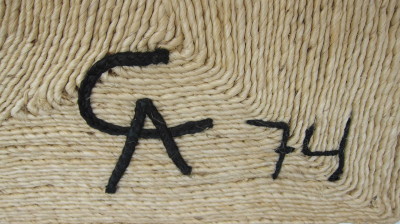

CALDER JUTE/MAGUEY FIBER WALL HANGINGS

Perhaps the most confusion when people talk about Calder tapestries comes from the series of mats that were created as part of a charitable relief program to help victims of a devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua. Kitty Meyer, a New York socialite, had brought Calder a thank you gift of a hammock braided by the artisans in the village of Masaya employing a centuries-old technique. The material used was not the fine wool employed by the ateliers of Aubusson and other famous tapestry centers, but natural vegetable fibers that could be spun into strong, coarse threads. The material may be identified as being Jute, Hemp, Maguey, Raffia or even rope. Calder was intrigued by the process. After collaborating on some hammocks, he ultimately agreed to let artisans in Nicaragua and Guatemala similarly execute 14 of his designs as mats in editions of 100 (the craftsmen were paid four times their usual wage plus given the materials gratis).

Perhaps the most confusion when people talk about Calder tapestries comes from the series of mats that were created as part of a charitable relief program to help victims of a devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua. Kitty Meyer, a New York socialite, had brought Calder a thank you gift of a hammock braided by the artisans in the village of Masaya employing a centuries-old technique. The material used was not the fine wool employed by the ateliers of Aubusson and other famous tapestry centers, but natural vegetable fibers that could be spun into strong, coarse threads. The material may be identified as being Jute, Hemp, Maguey, Raffia or even rope. Calder was intrigued by the process. After collaborating on some hammocks, he ultimately agreed to let artisans in Nicaragua and Guatemala similarly execute 14 of his designs as mats in editions of 100 (the craftsmen were paid four times their usual wage plus given the materials gratis).

Part of the problem with these mats (originally people put them on the floors of their rec rooms and porches) is that some of the designs were the same ones that had been used for Aubusson tapestries. If you looked at one of these mats next to an Aubusson tapestry and felt the materials, the difference in quality would be immediately apparent. However, if you had no familiarity with tapestries and wanted to get an idea of what your Calder maguey fiber mat might be worth, you might turn up a picture (and a price tag) of the Calder Aubusson with the same image and think you had hit the jackpot. And once prices for these mats escalated into the thousands, galleries bought them from people who had them on their floors and sold them as tapestries to people who put them up on their walls.

Part of the problem with these mats (originally people put them on the floors of their rec rooms and porches) is that some of the designs were the same ones that had been used for Aubusson tapestries. If you looked at one of these mats next to an Aubusson tapestry and felt the materials, the difference in quality would be immediately apparent. However, if you had no familiarity with tapestries and wanted to get an idea of what your Calder maguey fiber mat might be worth, you might turn up a picture (and a price tag) of the Calder Aubusson with the same image and think you had hit the jackpot. And once prices for these mats escalated into the thousands, galleries bought them from people who had them on their floors and sold them as tapestries to people who put them up on their walls.

Perhaps a bigger problem is that the Calder Foundation pictures several of these fibre hammocks and mats in the “Misattributed” section of their website, maintaining that Kitty Meyer was not authorized to make editions and that duplicate numbered pieces have been brought to their attention.

It’s comforting to think that every art professional is an expert who knows everything about everything, but misinformation percolates into world through innocence more often than deception. Though it has become rarer in recent years, you can still find these Calder fiber mats misidentified in both galleries and auction houses. This becomes an even more difficult problem with online auctions. It can be very hard to tell whether a “tapestry” is a maguey fiber mat or an Aubusson from a little tiny picture. Also, more and more retail sellers are turning to auction format because of the public perception that they will invariable get things cheaper at auction. Even if a Calder “tapestry” has been identified as one of these wall-hanging and not an Aubusson, the estimate from some online auctions may in fact reflect a retail price range, not an auction value.

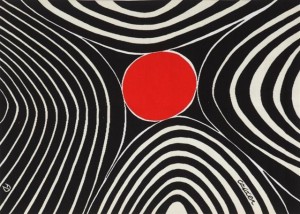

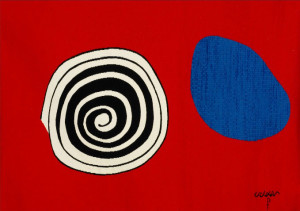

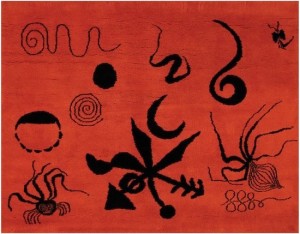

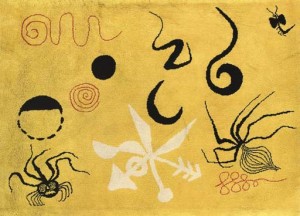

Take a look at the images below. The top piece is the Calder Aubusson tapestry Sillons Noirs from the edition of 6. The visual beneath is a maguey fiber mat sometimes identified as Zebra, an edition of 100.

This is a case where the confusion could have benefited a knowledgeable buyer. Over the past five years one Sillons Noirs Aubusson sold for about $12,000 and another passed at about $13,000, albeit in obscure French sales. The apparently faded maguey fiber wall hanging at the bottom — sold (albeit in Australia) for over $15,000. Another copy of this very same hanging sold at Phillips in London January 22, 2015, for about $3,000.

CALDER RUGS AND CARPETS (TAPIS)

The second biggest source of confusion when it comes to Calder tapestries are pile carpets and rugs, which the French call “tapis.” These are very graphic and people (including Calder himself) hang them on walls, so inevitably they are called tapestries.

The second biggest source of confusion when it comes to Calder tapestries are pile carpets and rugs, which the French call “tapis.” These are very graphic and people (including Calder himself) hang them on walls, so inevitably they are called tapestries.

In the book, Calder’s Universe, which was published in conjunction with the Whitney Museum’s 1976 Calder Retrospective, several rugs are pictured, some hooked and knotted by Louisa Calder, the artist’s wife, others by apparent friends of the family. These are identified as never being available for sale, only for personal use. In that anyone who knows how to make a rug (including commercial manufacturers who haven’t heard about artist’s rights) could conceivably make one after a Calder design, provenance can play an important part in determining whether a Calder rug is even legal.

There were two or three Calder tapis that were legitimately created by Marie Cuttoli, a friend of many artists including Picasso. Cuttoli had rugs made after Calder paintings she owned. Hand-knotted in India, these were originally sold in galleries both in Europe and the United States, but always for prices much less than Aubussons. While people generally assume that these were limited editions there were probably dozens created. And, as can be seen from the visuals, color seems to have been a matter of debate.

PROBLEMATIC CALDER TAPESTRIES

Problematic doesn’t necessarily mean illegitimate, it simply means there are problems. One such problem is how to figure out whether a price is a bargain or an outrage without comparable sales data. The less known a work is, the bigger the problem. A legitimate Calder tapestry was actually woven of goat hair in the African country of Lesotho. Good luck in figuring out what is a fair price for one (and such an item might be hard to r esell if you are thinking of buying it as an investment).

esell if you are thinking of buying it as an investment).

As explained above, Calder rugs and carpets can be problematic because, with the exception of the Marie Cuttoli pieces, there is scant information about who created Calder tapis, when they were made and whether they were authorized.

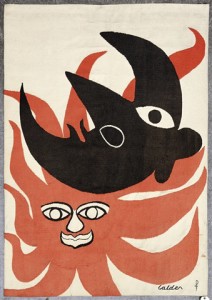

The biggest problems come from items that were created without permission whether innocently (a lot of little old ladies who admire Calder know how to hook rugs) or perhaps deliberately created to deceive. Take a look at the tapestry above. It appears to be a weaving of “Les Masques” a very good Calder Aubusson, one of which is owned by the Whitney Museum and is illustrated in Calder’s Universe.

If you saw this image in a catalogue or on a gallery’s website and were in the market for a Calder tapestry, this would seem to be a good choice, even at a high price. But you might be in for a surprise. Only when you received the tapestry will you notice that it is not a tapestry at all, it is a pile carpet.

I have no idea how this pile rug after the Calder Aubusson came to be made or who created it. And this isn’t the only Calder rug pretending to be an Aubusson that I’ve seen. Perhaps they might even have been authorized in some way, but I wouldn’t want to be the one who shelled out a lot of money with the hope that the Calder Foundation knew all about it.

The bottom line is that buying tapestries can be just as confusing and potentially treacherous as buying any kind of art. It’s important to understand what you’re doing or to be dealing with someone who does. And it may not be wise to rely on a seller’s expertise alone: someone who has something to sell always has a built-in conflict of interest when it comes to what’s best for the buyer.