All Calder Tapestries Are Not Created Equal

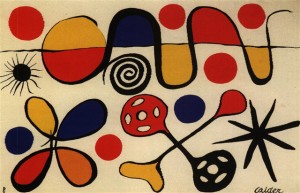

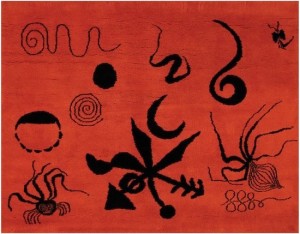

Alexander Calder (American, 1898 – 1976) may be best known for his stabliles and hanging mobiles but he also worked in almost every medium imaginable — paintings, prints, jewelry, stage sets and wire sculpture — he even decorated airplanes.

Beginning in the 1960s Calder aligned himself with important French weavers, most notably Pinton, which recreated his designs in fine art tapestry. Calder’s work was graphic, simple and perfectly suited to the medium, which made it both highly desirable to art buyers and profitable for the tapestry ateliers. Ultimately there were more tapestries by Calder than by nearly any other well-known artist.

“Les Passoires,” the most expensive Calder recorded at auction sold in 2007 for the equivalent of $77,810 without premium. Six years later in 2013 another copy from the edition sold for $5,000 less — premium included.

Some dealers now are asking over a hundred thousand dollars for Calder Aubusson tapestries, though they certainly can be found for less — not just because of the number available (there were over 60 different Calder designs made into small-edition Aubussons), but because there is a lot of confusion in the market place about this lesser-known medium. These days people use the word “tapestry” to refer to any textile that can be hung on a wall for decoration. You can take a blanket off your bed, tack it up over the window and call it a tapestry — no Vocabulary Police will arrive to arrest you. Consequently some types of Calder “tapestries” are worth a lot more than others.

There are basically five types of what people call “Calder tapestries”: 1) Aubussons; 2) Bicentennial Aubussons; 3) Natural Fiber Wall Hangings; 4) Pile rugs and carpets (tapis); and 5) Problematic Items

CALDER AUBUSSON TAPESTRIES

The tradition of weaving textiles goes back to ancient times. Horizontal stands of wool (or other material) called weft threads are passed between vertical warp strands that are affixed to a wooden frame called a “loom.” Colors are changed to create patterns or images. The resulting textile are called tapestries. The “Sun King” of France, Louis XIV, set up Manufactures Royales like the Gobelins to weave tapestries in this tradition for his palace at Versailles, and French tapestries woven in this manner are generically called “Aubussons.” Aubusson is actually a town in central France, which Louis declared a “Manufacture Royale” in 1665. Its output, and the output of ateliers in its sister city of Felletin (declared a Manufacture Royale in 1689) has always been commercially available and tightly controlled for quality.

A smaller ( 66 x 49 inches) and less colorful Calder Aubusson sold in November 2013 at a more obscure French auction for a hammer price of about $4,000.

It can take a skilled weaver a month to create a square meter of a fine Aubusson, so these French textiles — handwoven in the most famous tapestry ateliers in the world — have always had intrinsic value. Supply and demand has resulted in people willing to a premium above the weaving costs for images by important artists.

Some of the differences in pricing of Calder Aubussons has to do with basic considerations such as size. Large tapestries tend to cost more than small ones since their original retail cost was higher because they took longer to weave. Sometimes, however, very large tapestries can be difficult to resell because there are fewer potential buyers with giant walls. This is one factor that makes auction prices for tapestries so deceptive. There is very definitely a “sweet spot” in terms of size — if it’s too big or too small fewer people will bid.

Quality is also a factor. Buyers are sometimes more attracted to busier, more colorful images, but sometimes art can be too busy and too colorful. Or too quiet and not colorful enough. It’s a matter of taste and trends. Calder is much more popular now than he was twenty five years ago and Calder Aubussons are very much in demand.

CALDER BICENTENNIAL AUBUSSONS

1976 was the two hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Bi-Centennial. As part of the celebration a special series of 6 different Calder Aubussons was commissioned. Aubusson tapestries are limited in France to editions of no more than 6 with two authorized proofs — a maximum total of eight pieces. What made the Calder Bicentennial tapestries special is that the French government in the spirit of celebration allowed 200 sets to be woven. It was a magnanimous gesture — and an optimistic one.

eight pieces. What made the Calder Bicentennial tapestries special is that the French government in the spirit of celebration allowed 200 sets to be woven. It was a magnanimous gesture — and an optimistic one.

Only about 45 sets were actually ever made, which leads to confusion about supply in both directions. People have assumed that since the Bicentennial tapestries are Aubussons they must be editions of only six. Others assume that there were actually 200 tapestries made of each design. Whether 8, 45 or 200 were made, demand is actually more important in the pricing of tapestries (and most art) than supply. The Bi-Centennial Calder Aubussons are physically smaller and the designs generally less complex and graphically interesting than the most desirable Aubussons, so there is less demand and prices usually are significantly lower.

Bottom line: Depending upon the asking price, Calder Bicentennial tapestries may or may not be the bargains they seem to be.

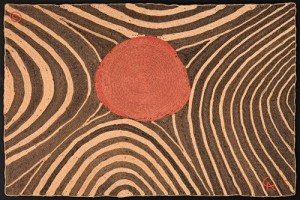

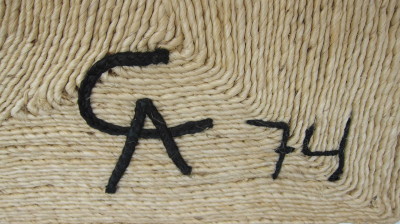

CALDER JUTE/MAGUEY FIBER WALL HANGINGS

Perhaps the most confusion when people talk about Calder tapestries comes from the series of mats that were created as part of a charitable relief program to help victims of a devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua. Kitty Meyer, a New York socialite, had brought Calder a thank you gift of a hammock braided by the artisans in the village of Masaya employing a centuries-old technique. The material used was not the fine wool employed by the ateliers of Aubusson and other famous tapestry centers, but natural vegetable fibers that could be spun into strong, coarse threads. The material may be identified as being Jute, Hemp, Maguey, Raffia or even rope. Calder was intrigued by the process. After collaborating on some hammocks, he ultimately agreed to let artisans in Nicaragua and Guatemala similarly execute 14 of his designs as mats in editions of 100 (the craftsmen were paid four times their usual wage plus given the materials gratis).

Perhaps the most confusion when people talk about Calder tapestries comes from the series of mats that were created as part of a charitable relief program to help victims of a devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua. Kitty Meyer, a New York socialite, had brought Calder a thank you gift of a hammock braided by the artisans in the village of Masaya employing a centuries-old technique. The material used was not the fine wool employed by the ateliers of Aubusson and other famous tapestry centers, but natural vegetable fibers that could be spun into strong, coarse threads. The material may be identified as being Jute, Hemp, Maguey, Raffia or even rope. Calder was intrigued by the process. After collaborating on some hammocks, he ultimately agreed to let artisans in Nicaragua and Guatemala similarly execute 14 of his designs as mats in editions of 100 (the craftsmen were paid four times their usual wage plus given the materials gratis).

Part of the problem with these mats (originally people put them on the floors of their rec rooms and porches) is that some of the designs were the same ones that had been used for Aubusson tapestries. If you looked at one of these mats next to an Aubusson tapestry and felt the materials, the difference in quality would be immediately apparent. However, if you had no familiarity with tapestries and wanted to get an idea of what your Calder maguey fiber mat might be worth, you might turn up a picture (and a price tag) of the Calder Aubusson with the same image and think you had hit the jackpot. And once prices for these mats escalated into the thousands, galleries bought them from people who had them on their floors and sold them as tapestries to people who put them up on their walls.

Part of the problem with these mats (originally people put them on the floors of their rec rooms and porches) is that some of the designs were the same ones that had been used for Aubusson tapestries. If you looked at one of these mats next to an Aubusson tapestry and felt the materials, the difference in quality would be immediately apparent. However, if you had no familiarity with tapestries and wanted to get an idea of what your Calder maguey fiber mat might be worth, you might turn up a picture (and a price tag) of the Calder Aubusson with the same image and think you had hit the jackpot. And once prices for these mats escalated into the thousands, galleries bought them from people who had them on their floors and sold them as tapestries to people who put them up on their walls.

Perhaps a bigger problem is that the Calder Foundation pictures several of these fibre hammocks and mats in the “Misattributed” section of their website, maintaining that Kitty Meyer was not authorized to make editions and that duplicate numbered pieces have been brought to their attention.

It’s comforting to think that every art professional is an expert who knows everything about everything, but misinformation percolates into world through innocence more often than deception. Though it has become rarer in recent years, you can still find these Calder fiber mats misidentified in both galleries and auction houses. This becomes an even more difficult problem with online auctions. It can be very hard to tell whether a “tapestry” is a maguey fiber mat or an Aubusson from a little tiny picture. Also, more and more retail sellers are turning to auction format because of the public perception that they will invariable get things cheaper at auction. Even if a Calder “tapestry” has been identified as one of these wall-hanging and not an Aubusson, the estimate from some online auctions may in fact reflect a retail price range, not an auction value.

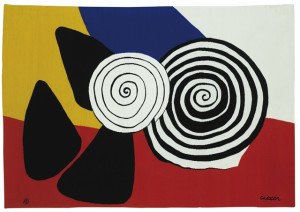

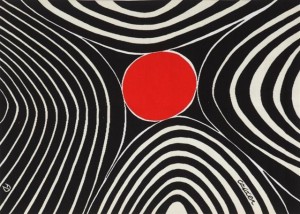

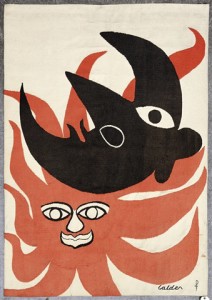

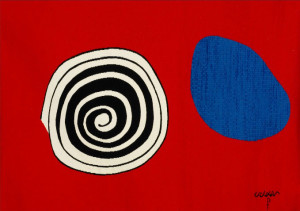

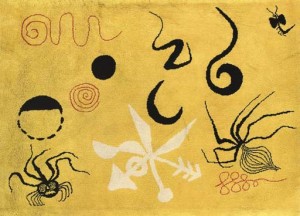

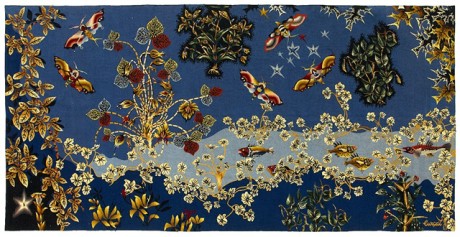

Take a look at the images below. The top piece is the Calder Aubusson tapestry Sillons Noirs from the edition of 6. The visual beneath is a maguey fiber mat sometimes identified as Zebra, an edition of 100.

This is a case where the confusion could have benefited a knowledgeable buyer. Over the past five years one Sillons Noirs Aubusson sold for about $12,000 and another passed at about $13,000, albeit in obscure French sales. The apparently faded maguey fiber wall hanging at the bottom — sold (albeit in Australia) for over $15,000. Another copy of this very same hanging sold at Phillips in London January 22, 2015, for about $3,000.

CALDER RUGS AND CARPETS (TAPIS)

The second biggest source of confusion when it comes to Calder tapestries are pile carpets and rugs, which the French call “tapis.” These are very graphic and people (including Calder himself) hang them on walls, so inevitably they are called tapestries.

The second biggest source of confusion when it comes to Calder tapestries are pile carpets and rugs, which the French call “tapis.” These are very graphic and people (including Calder himself) hang them on walls, so inevitably they are called tapestries.

In the book, Calder’s Universe, which was published in conjunction with the Whitney Museum’s 1976 Calder Retrospective, several rugs are pictured, some hooked and knotted by Louisa Calder, the artist’s wife, others by apparent friends of the family. These are identified as never being available for sale, only for personal use. In that anyone who knows how to make a rug (including commercial manufacturers who haven’t heard about artist’s rights) could conceivably make one after a Calder design, provenance can play an important part in determining whether a Calder rug is even legal.

There were two or three Calder tapis that were legitimately created by Marie Cuttoli, a friend of many artists including Picasso. Cuttoli had rugs made after Calder paintings she owned. Hand-knotted in India, these were originally sold in galleries both in Europe and the United States, but always for prices much less than Aubussons. While people generally assume that these were limited editions there were probably dozens created. And, as can be seen from the visuals, color seems to have been a matter of debate.

PROBLEMATIC CALDER TAPESTRIES

Problematic doesn’t necessarily mean illegitimate, it simply means there are problems. One such problem is how to figure out whether a price is a bargain or an outrage without comparable sales data. The less known a work is, the bigger the problem. A legitimate Calder tapestry was actually woven of goat hair in the African country of Lesotho. Good luck in figuring out what is a fair price for one (and such an item might be hard to r esell if you are thinking of buying it as an investment).

esell if you are thinking of buying it as an investment).

As explained above, Calder rugs and carpets can be problematic because, with the exception of the Marie Cuttoli pieces, there is scant information about who created Calder tapis, when they were made and whether they were authorized.

The biggest problems come from items that were created without permission whether innocently (a lot of little old ladies who admire Calder know how to hook rugs) or perhaps deliberately created to deceive. Take a look at the tapestry above. It appears to be a weaving of “Les Masques” a very good Calder Aubusson, one of which is owned by the Whitney Museum and is illustrated in Calder’s Universe.

If you saw this image in a catalogue or on a gallery’s website and were in the market for a Calder tapestry, this would seem to be a good choice, even at a high price. But you might be in for a surprise. Only when you received the tapestry will you notice that it is not a tapestry at all, it is a pile carpet.

I have no idea how this pile rug after the Calder Aubusson came to be made or who created it. And this isn’t the only Calder rug pretending to be an Aubusson that I’ve seen. Perhaps they might even have been authorized in some way, but I wouldn’t want to be the one who shelled out a lot of money with the hope that the Calder Foundation knew all about it.

The bottom line is that buying tapestries can be just as confusing and potentially treacherous as buying any kind of art. It’s important to understand what you’re doing or to be dealing with someone who does. And it may not be wise to rely on a seller’s expertise alone: someone who has something to sell always has a built-in conflict of interest when it comes to what’s best for the buyer.

Chagall (and other) Tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince

The name Yvette Cauquil-Prince is virtually synonymous with the term “Marc Chagall tapestry.”

After all, Chagall didn’t spend years mastering the ancient craft of weaving and then sit working at a loom, day after day, for months at a time. Someone else had to do that, and for Chagall — as with artists and their estates including Picasso, Leger, Calder, Kandinsky, Klee, Ernst, de St. Phalle, Brassai and Matta — it was Yvette Cauquil-Prince.

The Belgian-born Cauquil-Prince was Chagall’s best option to continue to explore the medium of tapestry which he had become enamored with after completing a series of tapestries commissioned by the state of Israel. The Chagall tapestries that still decorate the state reception hall of the Knesset had been woven by the Gobelins, the famous French “Manufacture Royale” which was set up by Louis XIV but to this day only takes on gifts of state. Happily Madeline Malraux, the wife of the France’s Cultural Minister Andre Malraux, was acquainted with Yvette Cauquil-Prince and made the introductions.

Chagall was wary at first, demanding that their first effort be destroyed if he didn’t like it. Yvette had a condition of her own — that it be destroyed if SHE found it wanting. Happily both were delighted, and they embarked on a long collaboration and friendship so close that Chagall referred to Yvette as his spiritual daughter. As had Picasso, the artist allowed Yvette to choose the images to be translated into tapestry and didn’t interfere with her interpretive cartooning or weaving as it progressed. After Chagall’s death Yvette remained close to the artist’s family and with their approval continued to create Chagall tapestries, something that Chagall himself had said he wanted. “When I am no longer here, you must continue the work,” he told her. “There will never be a tapestry by Chagall without you.”

Altogether there were only about forty Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince, some of them monumental in size, all of them very small editions or unique (though “editions of one” often provided for an artist proof reserved for the Chagall family). She didn’t actually weave most of these pieces herself. Early in her career Yvette had developed a complex shorthand code by which other weavers in her employ could execute her complex Coptic-influenced interpretative designs — the blueprints that made a Chagall tapestry a Chagall tapestry. By the end of her life in 2005 it could take Yvette up to a year to complete one of these “cartoons” for tapestry.

Cauquil-Prince was recognized by the Louvre as a great artist in her own right, and her Chagall tapestries are widely honored in important private and public collections throughout the world. Because such tapestries are much rarer than Chagall paintings the temptation is to call them “priceless” since they rarely come up for public sale. However, everything has its price and during her lifetime most of Cauquil-Prince’s tapestries were for sale (this was how she made her living). They come back onto the market from time to time.

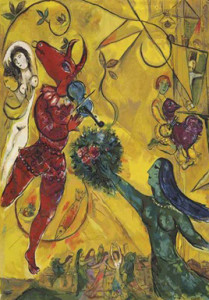

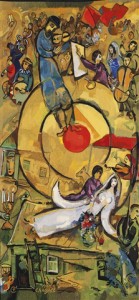

Two of arguably the most beautiful small Chagall tapestries recently appeared at auction. “Liberation” was withdrawn from Sotheby’s New York sale of November 7, 2013. Perhaps the consignor was nervous about it making the presale estimate of $200,000 – $300,000 and sold it privately before the auction. If so, he may have acted too quickly, judging by the very comparable “La Danse” tapestry, which sold at Christie’s London on February 5, 2015, for the equivalent of $306,621 USD. The presale estimate for La Danse was $152,928 – 229,392 USD, reflecting the lower prices that tapestries by other important artists have recently achieved. All tapestries are not created equal, of course. In the last ten years three other small Chagall tapestries by Yvette Cauquil-Prince have sold at auction at prices between about $30,000 – $80,000, and one monumental masterpiece brought $385,000 – still the auction record for a Chagall tapestry.

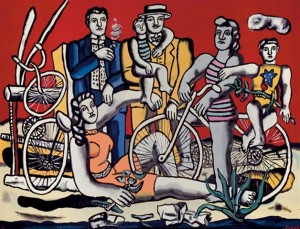

Cauquil-Prince and Chagall were so attuned that Chagall himself declared upon seeing one of her efforts, “This is a real Chagall. It is my hands that did all this.” Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Yvette’s Chagall tapestries sell for higher prices than her interpretations of the works of other artists. However, it would be hard to make a case that Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Leger’s “Les loisirs sur fond rouge” isn’t a spectacular tapestry. Why, then, did it sell at auction for 45% less than the top Chagall? It’s not like Leger is somehow a less important or desirable artist, at least in terms of public sales of paintings. The highest price for a Chagall painting at auction was $14,850,000 versus $39,241,000 for the top Leger lot. If you add up the top ten auction sales for each artist Leger still wins hands down — his top ten sales add up to nearly $176,000,000 versus just $100,000,000 for Chagall.

I often write about value mysteries and in many ways every sale of a work of art qualifies as a mystery. It’s no more strange that Yvette’s Chagall tapestries bring more at auction and than her Legers than the fact that Chagall tapestries are sometimes priced 1000% higher in galleries than they likely can be resold for at auction. However, the real mystery has to do with the tapestries that Yvette Cauquil-Prince created with Max Ernst.

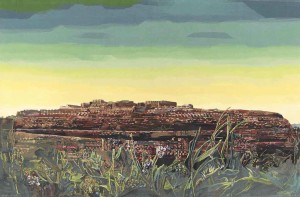

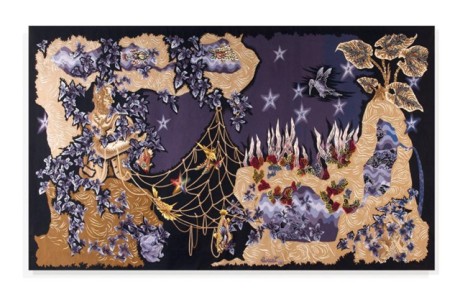

Monumental Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince: “La ville entière” – 111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches

Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976), was a German born Dadaist/Surrealist. His work can be seen numerous important museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, the Hirshhorn, Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and on and on. He sells well at auction. Ernst’s top sale was $16,322,500 vs, $14,850,000 for Chagall, though if you look at the top ten auction prices Chagall thrashes Ernst two to one (why auction prices can be hugely deceptive indicators will be to subject of a future post).

Yvette Cauquil-Prince’s collaboration with Max Ernst actually came about smack in the middle of her triumphant work with Chagall. Chagall called Yvette “my little girl” once too often in front of his jealous wife, Vava, and she banished Cauquil-Prince from working with her husband for a decade. In 1978 Yvette came back to Milwaukee where she had been greeted so warmly upon completion of the Jewish Museum’s Chagall, to present her ten Max Ernst masterpieces,which then toured to Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

Like her Chagall tapestries, Cauquil-Prince’s Max Ernst masterpieces were beautifully interpreted, monumental in scale and woven in very small editions, some of them unique. Because of the difficulty and time-consuming nature of the cartooning and because Cauquil-Prince had to maintain an entire atelier of artisans to weave her pieces on Corsica, it’s likely that the prices for the finished tapestries were comparable to what she had asked for her Chagalls.

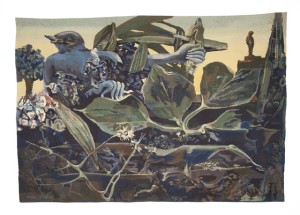

Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” tapestry (76.4 x 106.2 inches) woven by Cauquil-Prince did not fare well at auction

What makes an artist “important” and “desirable” doesn’t necessarily equate to demand across different markets. For collectors of Surrealism, important paintings by Ernst are very desirable. For an American living in the mid-West who is decorating his home, a beautiful tapestry by the famous Chagall is a lot more desirable than some beautifully weird and disturbing tapestry by Max Ernst, who is not exactly a household name in the USA. Still, you’d think that an Yvette Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestry would be worth at least half as much as a Chagall or even a Leger, wouldn’t you?

But you’d be wrong. Not to be cynical, but value doesn’t necessarily have much to do with price, whether at auction or in galleries (it was Oscar Wilde who wrote that “a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing”). The day after the small Chagall “La danse” sold in London for the equivalent of $308,000 against an estimate of 100,000 – 150,000 GBP, a monumental (111 7/8 x 169 1/2 inches) Cauquil-Prince Max Ernst tapestry, “La ville entière” was passed a few miles away at Christie’s South Kensington against an estimate of just 10,000 – 15,000 GBP — about $16,000 to $24,000!

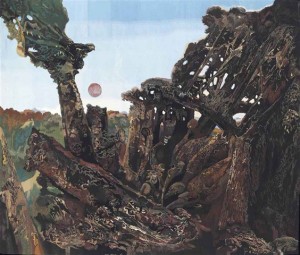

“Totem et Tabou” – Max Ernst tapestry by Yvette Cauquil-Prince measuring a gigantic 163.4 x 194.9 inches

It’s tempting to think that this was some kind of bizarre fluke, but in fact Cauquil-Prince tapestries by Max Ernst have a history of making prices vastly lower than what it would cost to weave them. Christie’s didn’t just pull their estimate out of a hat, it was probably based on Cauquil-Prince’s weaving of Ernst’s “La nature à l’aurore” which sold at Sotheby’s New York on December 15, 2014 for just $22,500. And it’s not like Sotheby’s was throwing their piece away — they had offered it at an estimate of $25,000 – $35,000 on May 8, 2013 and it had failed to sell (it had brought $36,000 at a 2006 Christie’s sale). “Totem et Tabou,” which is the largest and arguably the most important of Cauquil-Prince Ernst tapestries, was passed at Christie’s London on February 7, 2013 with a much more aggressive estimate — 50,000 – 70,000 GBP (78,480 – 109,872 USD).

Bottom line, there just isn’t much demand for Max Ernst tapestries, Yvette’s talent notwithstanding, which to my mind makes them fantastic bargains (provided you like the work of Max Ernst). But auction results can be extremely deceptive indications of prices in the real world. Unless you have a time machine, knowing what was available last year (or yesterday) isn’t worth much. For thinly traded items like tapestries, the “spread” between bid and ask prices can vary wildly. Yes, “La ville entière” may have failed to get a $16,000 bid at Christie’s but it was snapped up within days after the sale. It may very well show up in some dealer’s possession tomorrow with an asking price of hundreds of thousands of dollars, which may be what it really is “worth” but would make it no bargain at all.

Value Mysteries: Jean Lurçat Tapestry Screen

Most dealers and auction houses don’t have a lot of knowledge about tapestries by 20th centuries artists. This makes for a very inefficient, thinly traded market — exactly the type of environment in which smart people can make big profits. Aubussons by Alexander Calder are sometimes still estimated for $2,000 – $3,000 as they were twenty years ago. Though the final hammer prices generally are much higher if word gets out, sometimes no one recognizes what bargains can be had.

Calder didn’t sit down at a loom for months weaving those “Calder” tapestries, of course. He didn’t even see most of them — tapestries are multiples, and Aubussons were generally woven in editions of six with two authorized artist proofs. Long after Calder died, the ateliers were still completing these editions.

It wouldn’t be correct to call tapestry ateliers “factories,” but since they were established by Louis XIV in the 17th Century the “Manufactures Royales” of Aubusson have been businesses that must charge a certain amount per square foot in order to cover salaries, cost of materials, administrative overhead, payment to the artist and profit. Sometimes the marketplace bestows a premium above and beyond what it would cost to replace a tapestry from the weaver. This is especially true for tapestries by Brand Name artists like Picasso, Chagall, Miro, Leger that were woven years ago and the editions are closed out. Here, the line between decorative art and fine art begins to blur and tapestries become rare and collectible artifacts, like first editions by important authors. Tapestries by lesser-knowns, on the other hand, can sometimes be purchased for a fraction of their replacement cost — like used books by forgotten writers.

This tapestry by Saint Saens, an artist influenced by Lurcat, was recently on sale in a retail gallery for less than $10,000

One of the most important names in the tapestry world of the mid-20th century was French artist Jean Lurçat. Lurçat was not a weaver himself but he became a master of the medium and inspired scores of important French artists of the period to work in tapestry, which had been a dying art form.

Between 1900 and 1910 the average annual output of the world-famous Beauvais tapestry workshops was a mere 20 square metres because the weaving costs had risen as high as 38,000 francs per square metre, roughly $60,000 in today’s dollars! Lurçat rescued the Aubusson tapestry ateliers practically single-handedly by simplifying design and production requirements. His innovations brought costs back down to earth and the Aubusson ateliers sprang to life in the 1940s once weaving became profitable again.

Lurçat, however, is not a name known to most Americans. His tapestries and those by important artists who followed his lead are usually sold as decorative pieces with none of the fine art premium that attaches to Calders, Sonia Delaunays and the like. Thus beautiful tapestries by René Perrot, Jean Picart le Doux, Mario Prassinos and Jean Lurçat himself can be found in retail galleries for prices in four figures – far less than the cost of weaving, which it could be argued is their intrinsic value.

Fine art tapestries like other works of art are not commodities. One Miro tapestry is not the same as any other any more than all Picasso paintings are interchangeable in value like pork bellies or ounces of silver. Nor are auction prices reliable indicators of value, though they can provide useful insights.

Take this Lurçat tapestry for instance. “Papillons de Nuits” is a large, fairly typical Lurçat measuring 68.1 x 135.8 inches. It sold under estimate at the Van Ham Kunstauktionen auction in Germany on 1 December 2011 for the equivalent of about $6,000.

“Papillons de Nuits” is a large, fairly typical Lurçat measuring 68.1 x 135.8 inches. It sold under estimate at the Van Ham Kunstauktionen auction in Germany on 1 December 2011 for the equivalent of about $6,000.

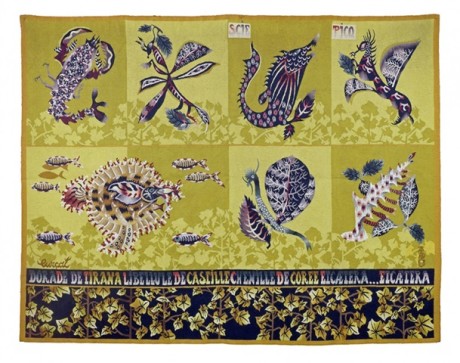

Here’s another, arguably a “better” Lurçat tapestry. Auction records show that “Scie Pick,” 60.2 x 120.5 inches, was passed at Éric Pillon Enchères auction in France of October 26, 2014 against an estimate of 7 – 8,000 Euros (8,868 – 10,135 USD). Another tapestry that looks just like this one but measured only 60.2 x 78.7 inches sold at Drouot-Estimations in Paris on June 13, 2014, for 4,100 EUR (5,544 USD) Hammer. While modern Aubussons are generally limited to a total of eight pieces as indicated above, select tapestries were sometimes “re-editioned” in different sizes — a way of capitalizing on the more successful images (and making them not quite as “rare” as edition sizes would seem to indicate).

Here’s another, arguably a “better” Lurçat tapestry. Auction records show that “Scie Pick,” 60.2 x 120.5 inches, was passed at Éric Pillon Enchères auction in France of October 26, 2014 against an estimate of 7 – 8,000 Euros (8,868 – 10,135 USD). Another tapestry that looks just like this one but measured only 60.2 x 78.7 inches sold at Drouot-Estimations in Paris on June 13, 2014, for 4,100 EUR (5,544 USD) Hammer. While modern Aubussons are generally limited to a total of eight pieces as indicated above, select tapestries were sometimes “re-editioned” in different sizes — a way of capitalizing on the more successful images (and making them not quite as “rare” as edition sizes would seem to indicate).

Auction prices can be greatly misleading, and it would be foolish to believe that somehow $5,000 or $6,000 “should” be the price of a Lurçat tapestry. In fact they have sold at much higher prices both at auction and in galleries.

Jean Lurçat’s

“Chasse et pêche” measuring 81 x 140 inches sold at a French auction in 2011 for the equivalent of $44,000 – probably less than it would cost to have a similar piece woven today. In a retail gallery it would be priced much higher.

It’s not likely that most people looking for a large artwork to place on a wall in their home would have been considering tapestries when the above pieces sold inexpensively at auction, nor is it likely that Americans would have even found these particularly obscure sales. Even if you have a time machine, it’s not like you can actually buy these tapestries for the recorded auction prices — you will simply be able to make the next bid. Unless the actual buyer then just gives up, the price could go much higher. In fact many Lurçats have sold for much more at auction and in galleries, which is where most tapestries are sold to end users. Retail buyers generally need someone to explain why a tapestry might be better for them than a painting and time to consider the type of image and the size that might work in their home.

But the fact is that Lurçat is not a “hot” artist. There is not much demand for tapestries in general, let alone for tapestries by Lurçat. This is why most sell — even in retail galleries — for less than it would cost to weave them. To some people that would indicate “value” and “bargain.” Others would probably be thinking “White Elephant.”

So what would you call this Lurçat tapestry screen that I saw recently in the booth of a fashionable French gallery at a high end art and antiques fair in New York?

While it appears at first to be an eight panel screen, closer examination reveals that it is actual four two-piece panels, making it much easier to transport and set up. Actually it’s a pretty ingenious thing to do with very large horizontal tapestries like the ones illustrated above, which generally are harder to sell than smaller pieces which can be more easily placed. In fact this screen is 90.5 x 220.5 inches — over 18 feet across!

While it appears at first to be an eight panel screen, closer examination reveals that it is actual four two-piece panels, making it much easier to transport and set up. Actually it’s a pretty ingenious thing to do with very large horizontal tapestries like the ones illustrated above, which generally are harder to sell than smaller pieces which can be more easily placed. In fact this screen is 90.5 x 220.5 inches — over 18 feet across!

Such a huge tapestry was probably commissioned for a specific space — this is not the type of thing you weave on spec and then hope to find someone with a gigantic room they want to hang a tapestry in. Perhaps when the original owner died somebody needed to be creative in order to sell this gigantic thing and had it mounted. However, the woman in the booth at the fair explained imperious tone that this was designed by Lurçat specifically to be a screen, in fact it was the only such screen he ever created.

When I asked if there was some documentation for this claim I was given the look that dealers reserve for Martians and other ignoramuses. Obviously if I were one of those crazy Americans obsessed with minutia, I wasn’t a likely prospect to buy anything. Especially a rare tapestry screen like this one priced at $160,000!

Well, maybe the story was true, maybe it wasn’t. However, the bottom line of value is always determined by supply and demand. There were hundreds, possibly thousands of Lurçat tapestries woven; few people are looking specifically for this type of thing, hence prices are often below intrinsic cost. However, this smart French dealer is trying to change the equation. He’s saying that the supply is not thousands but — if you believe the story — only one. And while demand by knowledgeable buyers of tapestries for an impossibly large Lurçat is minimal, a lot of rich people on Park Avenue with big walls and collectors of trendy Mid-Century Modernism shop at prestigious art and design fairs. They’ve probably never seen anything like this (partly because they don’t shop in those places where Lurçat tapestries can be purchased for less than $10,000).

Whether the screen sold for anywhere near the asking price or at all, I do not know. What I do know is that somebody bought this very same Lurçat at Sotheby’s Paris on November 26, 2013 for a little more than $20,000. The Value Mystery is whether the French dealer will be able to sell it, how long will it take, and how much will it finally bring? At full price somebody stands to make a 700% profit in a year, but that $160,000 probably is not a great deal higher than it would cost to weave such a tapestry today.

So what about this other Lurçat tapestry screen measuring a much more practical 89 x 32 inches that sold at the Leland Little Auction & Estate Sale of March 17, 2012, for a total price of $2,000? What kind of value should be placed on it?

So what about this other Lurçat tapestry screen measuring a much more practical 89 x 32 inches that sold at the Leland Little Auction & Estate Sale of March 17, 2012, for a total price of $2,000? What kind of value should be placed on it?