Unique Picasso Ceramics vs. Madoura Editions

The market for Edition Picasso ceramics is hot. The auction prices of some pieces have soared 500% and more from one year (or one sale) to the next.

I’ve discussed the reasons for this explosion of interest before (the Runaway Bull, the Runaway Bull Returns, the High-Flying Owl), reminding people that the Edition Picasso Ceramics were not personally painted by Picasso. Though Picasso decorated over 4,000 ceramics, the Edition Picasso is comprised of some 600 “authentic replicas” recreated after Picasso’s unique prototypes by the artisans at the Madoura pottery in the South of France.

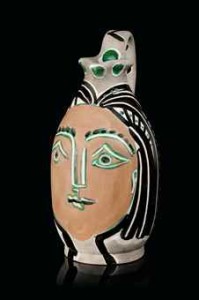

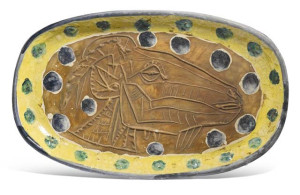

This Edition Picasso “Tête de chèvre de profil” AR 148 sold at Sotheby’s Paris on May 21, 2015, for $19,468.

When people hear about this distinction their initial reaction is often that they don’t want to buy “reproductions,” only originals. Unfortunately original Picasso paintings can cost as much as $179,365,000 at auction. A desirable Edition Picasso ceramic can sell for 1/10,000th of that (the Goat plate illustrated above brought only 1/9,213th of the record painting price, but you get the idea). No wonder these multiples quickly became collectable after their introduction in 1948 when they were sold as inexpensive souvenirs to vacationing tourists. That’s right, Edition Picasso ceramics purchased for fifty dollars in the 1950s are today worth tens of thousands.

So you would figure that the ceramics that Picasso personally decorated would be a lot more valuable than the ones that were replicated, right? Well, yes and no. Yes, they’re worth more. But no, they’re not worth 10,000 times more, or even 1000 times more. Or even 100 times more. Or, often, even 10 times more. And some of them have recently sold for less than Edition pieces.

One reason for this anomaly is the very rarity of Picasso’s “original” ceramics, most which were never commercially available. People equate rarity with value, but prices are determined in the marketplace. Picasso kept the vast majority of the unique pieces for himself and most ended up in museums or with members of the artist’s family. Consequently, the kind of competition that makes prices rise never developed for originals – they rarely came up for sale. However as early as the 1970s the approximately 120,000 ceramics in the Edition Picasso began appearing at auction. If a collector wanted an Edition Picasso ceramic there was a huge selection immediately available, but if he wanted a ceramic that Picasso himself had painted he might wait years before one appeared. The very term “Picasso ceramic” came to mean one of the multiples replicated by the artisans at Madoura.

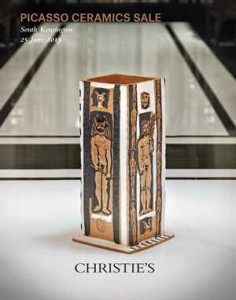

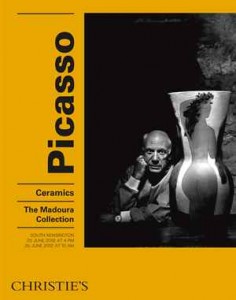

It’s therefore doubly difficult to compare values for unique Picassos and Edition Picasso pieces, since not only do auction results swing wildly from place to place and year to year, there just isn’t much comparable sales data. Because of a rare coincidence, however, we now have a unique opportunity to make such price comparisons. In London on June 25, 2015, Sotheby’s sold a collection owned by Marina Picasso of over 100 ceramics personally painted by her grandfather (Marina is the daughter of Picasso’s son Paulo and his first wife, Olga Khokhlova). On the same day in another part of town there was a dedicated sale of Edition Picasso ceramics – at Christie’s South Kensington, the venue that has accounted for many of the recent record-breaking sale prices.

While comparing apples and oranges is still easier than comparing most of the ceramics in these two sales, some pieces are directly equatable. For instance, take a look at these two pieces:

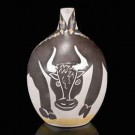

The one on the left is from the Edition Picasso, Picador et taureau, AR 194, from the edition of 200 (the “AR” number is from Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonné). The one on the right was entitled Tauromachie in Marina Picasso’s collection, a unique ceramic hand-painted by Picasso — almost certainly the prototype for the Edition piece.

The AR 194 Edition Picasso Picador et taureau plate brought the equivalent of about $10,780 at Christie’s South Kensington. At the Sotheby’s sale across town the comparable unique piece sold for the equivalent of $68,800. Granted that neither one of these ceramics is a great work of art. In fact if you had been at Madoura in 1953 the Edition piece was probably one of the Picasso tsotchkes priced at five or ten bucks. But if you use these two ceramics as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth 6.38 times more than the Edition Picasso piece.

However, another pair of ceramics tell a different story:

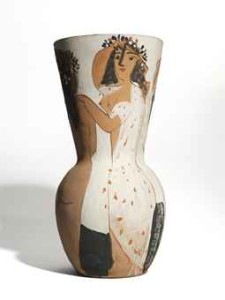

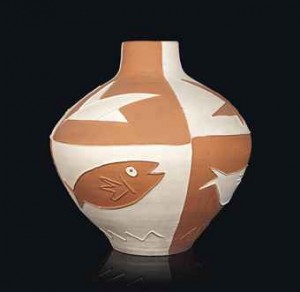

In the Christie’s sale, the AR 296 Edition Picasso ceramic, pictured on the left, sold for $27,440 (I’m using the auction houses’ conversions to translate all of these prices from pounds to dollars). The one of the right, one of Marina Picasso’s unique pieces, sold for $94,354 at Sotheby’s. The market — as well as your eyeballs — might suggest that these ceramics are “better” than the Picador plates. However, using these vases as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth only 3.43 times more than the copy. Why does a “better” original bring a smaller multiple?

In the Christie’s sale, the AR 296 Edition Picasso ceramic, pictured on the left, sold for $27,440 (I’m using the auction houses’ conversions to translate all of these prices from pounds to dollars). The one of the right, one of Marina Picasso’s unique pieces, sold for $94,354 at Sotheby’s. The market — as well as your eyeballs — might suggest that these ceramics are “better” than the Picador plates. However, using these vases as a guide, a Picasso “original” is worth only 3.43 times more than the copy. Why does a “better” original bring a smaller multiple?

The most expensive piece in Sotheby’s sale of Marina Picasso’s ceramics, by far, was described as a vase but seems more of a sculpture than the usual shapes and plates in the Edition Picasso. It sold for $762,698 and is pictured at the top of this page. No Edition Picasso ceramic is even remotely comparable to this piece. The top lot in the Christie’s sale was Femme du Barbu (the Bearded Man’s Wife), AR 193, which sold for $163,856. Using these two ceramics as a guide you might conclude that the best Picasso original is worth 4.65 times more than the best Edition Picasso multiple.

Of course it is worth noting that Femme du Barbu is hardly among the “best” Edition Picasso ceramics. For starters it’s an edition of 500, the largest edition size made. I’ve found 16 other sales of this ceramic since 2013 with an average sale price of about $30,000 (until the Madoura sale in 2012 they brought much less). Femme du Barbu was estimated in the Christie’s catalogue for about $19,000 – $28,000. In short, it’s a fairly large, very common ceramic, and it’s whimsical and fun. But you can say the same about many, many other pieces.

So in the interest of fairness let’s look at what actually is considered to be the “best” Edition Picasso ceramic because of its scale, rarity, beauty and renown: the Grand Vase, AR 116. This ceramic is over ten inches larger than Femme du Barbu, it’s from an edition of just 25 (the smallest produced), it is pictured on the cover of the Alain Ramié’s catalogue raisonné and in a famous photograph of Picasso by Henri Cartier-Bresson. One of these pieces made the auction record for an Edition Picasso ceramic: $1,144,268 at the much hyped “Madoura” sale in 2012. Another brought $1,080,221 in 2014. Thus using the Grand Vase as a guide, the best “original” Picasso ceramic in Marina Picasso’s collection was worth less than the best Edition Picasso piece!

Prototype for Picasso “Grand Vase” AR 116 which brought a record $1.5 million. One of the 25 Madoura Edition Picasso copies brought $1.14 million.

If you want to get picky, at $762,698 Marina Picasso’s unique vase pictured above isn’t the “best” unique Picasso ceramic ever to sell at auction, at least in terms of price. Ironically that honor belongs to Picasso’s prototype for the same Grand Vase that set the record for most expensive Edition Picasso ceramic. This prototype sold in 2013 at Christie’s in London for $1,534,557. In other words, the original sold for only 1.5 times more than the copy.

Clearly something is screwy here. Either Edition Picasso ceramics are overpriced, unique Picasso ceramics are underpriced, or a combination of both. To say nothing of the possibility that the entire art market may presently be in the same kind of mania that precedes stock market crashes (and the fact that it’s silly to try to draw conclusions from individual sales in thinly traded, inefficient markets).

Regardless of whether an entire market is elevated or depressed, however, certain ratios should be constant unless there is a fundamental paradigm shift as there was in the 1970s and 1980s due to the influx of Japanese buyers. In Western culture, oil painting is the most important fine art; ceramics are less important. In Asia it’s just the opposite. When the Japanese entered the market, they were willing to pay vastly higher prices for ceramics than anyone ever had before. When they stopped buying at the beginning of the 1990s, prices crashed.

Unique Picasso Goat plate from Marina Picasso’s collection sold at Sotheby’s in June 2015 for $176,914

Let’s return for a moment to that $179 million record-price Picasso painting, and the fact that you can get a fine Edition Picasso ceramic for about 1/10,000th of that. The Tête de chèvre (AR 148) platter from the edition of 100 pictured at the top of this page is an example of such a bargain at a sale price of $19,468. If you believe in numerology (and the metric system) you’ll be interested to learn that Picasso’s probable prototype for Tête de chèvre sold for $176,914 in the Marina Picasso sale at Sotheby’s, about ten times more than its Edition Picasso equivalent but close to 1/1,000th of the record-price Picasso painting.

So, how much more should unique Picasso ceramics be worth than comparable Edition Picasso pieces? If the answer is 1000 times, then the Grand Vase prototype should have brought at least a BILLION dollars — 1,000 times the $1+ million that the two Edition Picasso Grand Vases have recently sold for. If the answer is 100 times, then the best originals should be somewhere between $50 and $100 million — 100 times the $500,000+ prices that many other Edition Picasso Grand Vases have brought at auction. If it’s a mere 10 times, as the the two  Goat plates would seem to suggest, then best original Picasso ceramics should sell in the $10,000,000 range. If the other examples compared above are better guides, then the best unique pieces should be $6,380,000 or $3,430,000, 0r $4,650,000 — in all cases significantly more than they have actually been selling for. To my mind the buyer of the beautiful Picasso at the top of the page got a steal.

Goat plates would seem to suggest, then best original Picasso ceramics should sell in the $10,000,000 range. If the other examples compared above are better guides, then the best unique pieces should be $6,380,000 or $3,430,000, 0r $4,650,000 — in all cases significantly more than they have actually been selling for. To my mind the buyer of the beautiful Picasso at the top of the page got a steal.

Clearly Christie’s believed that the “best” Edition Picasso ceramic in their sale of June 25, 2015, was Personnages et Têtes AR 242. At 22 inches tall, not only was it the largest piece in the sale, it was one of only 25, the smallest edition size produced at Madoura. It was pictured on the cover of the catalogue and brought the second highest price in the sale (after the outlier Femme du Barbu ), selling for $145,040 — over twice its low estimate ($62 ,000 – $92,000). Yet more than half of the unique Picasso ceramics from Marina Picasso’s collection at Sotheby’s sold for less than the cost of this Edition Picasso multiple. Granted that the originals were smaller in size and arguably less interesting than Personnages et Têtes, but they were actually from the artist’s hand, not “authentic replicas.”

Which would you rather own?

Value Mysteries: Picasso Ceramic Owls

In 1946 Picasso was staying near Antibes in the South of France and decorating the walls of what would become the Musée Picasso. A small owl with an injured claw that had been found in a corner ended up living with him and his lover, Francois Gilot. According to Gilot in her book “Life With Picasso” the owl was an ill-tempered creature who smelled awful and ate only mice. The owl would snort at Picasso and bite his fingers; Picasso would reply with a string of obscenities just to show the bird who was the most ill-tempered. Clearly bad manners were the way to Picasso’s heart for not only did he do a number of paintings, drawings and prints of owls, he created numerous ceramics.

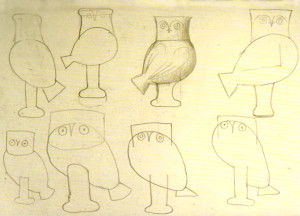

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

While it is true that Picasso didn’t create most of the ceramic shapes that he decorated at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris (though he did manipulate many of the forms — bent them to his will, if you will), it was not until after the artist’s death did sketches come to light that proved Picasso had in fact executed designs for ceramics around the time the little owl was regurgitating hairballs around the house.

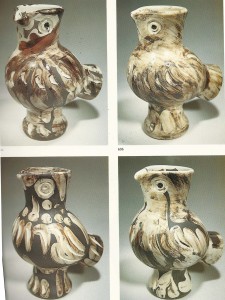

Take a look at five ceramics below that were created at Madoura in 1951. One of them was painted personally by Picasso. The others were painted by the artisans at the pottery after Picasso’s original, what are called “authentic replicas” in the Ramié catalogue raisonne and what are commonly known as Edition Picasso Ceramics. Can you tell which is the one painted by the artist?

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

This isn’t the value mystery by the way, although Picasso’s unique prototypes usually command prices at least ten times higher than the editions. We’ll get to the value mystery shortly. First, however, it will be useful to understand how relatively common this owl shape was in the entire set of 633 Picasso ceramics that were made into editions.

Of the edition owls above one was of 500 (Picasso ceramics were made in editions of between 25 and 500), so it is not particular rare. The other three were from editions of 300, so already in 1951 there were 1400 owls of this shape flying out of Madoura. You might think that there were really 1401 counting the one that is Picasso’s unique piece, but you would be wrong. In addition to the unique piece (the fourth in the lineup above) which was not made into an edition, there were prototypes for the four other owls that were replicated plus, undoubtedly, other paintings by the artist of this shape. The essence of Picasso’s genius was his being able to tap into a virtually inexhaustible creativity. Once the artisans at the Madoura pottery had created Picasso’s owl shape in ceramic they would have given him some fired pieces which he would have begun decorating. It was not unusual for Picasso to paint a dozen ceramics in a day or more. Altogether he painted over 4000 pieces at Madoura, only 633 of which were made into editions.

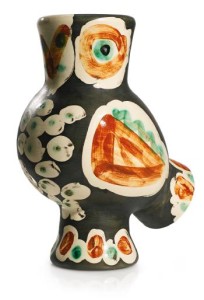

There were other owl shapes decorated by Picasso but this, his own, clearly remained one of Picasso’s favorites. A new edition of 300 differently painted owls of this same shape were produced in 1952. In 1958 another edition was created, this one of 200 pieces (the smallest edition of this particular form), not with a white glaze but just the terracotta clay as the mat finish. Ten years later, in 1968, Picasso decorated two more owls in his most complex and colorful design, each editions of 500. A year later, in 1969 just a few years before his death Picasso returned to the shape again with six new pieces — some of his last ceramics, also in large editions. If you add up all the edition owls of this particular shape the total comes to 5,250. Since some shapes were painted just once by Picasso in editions as small as 25, it is safe to say that these owls not only are not rare, they are actually among the most common of the three-dimensional Edition Picasso ceramics.

Now consider these four different versions of the form — all from 1969 — and therein lies the mystery:

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

These owls are regularly estimated at about $6000 – 8000 at auction. However, one of them — or I should say a piece from one of these editions — sold at Sotheby’s London on March 19, 2013, for the equivalent of $75,590.

Was that particular version some kind of weird rarity? No, it was simply one of the 500 copies in the edition, which are all supposed to be virtually identical replicas of Picasso’s prototype. Is one of these versions somehow “better” than the others from 1969 (or all the other 5,249 Edition Picasso owls of this shape)? No. In fact these four ceramics are often miscatalogued because they resemble one another so closely and because of their muddy palette they have historically sold for less than some of the more colorful pieces of the same form.

So what gives?

I have spoken about the wild price fluxuations in Picasso Ceramics before, which started with the “Madoura” sale at Christie’s London in June 2012. A lot of it boils down to a thinly traded market, lack of information and clever people trying to exploit one another. The $75,590 owl was Ramié 605, the first owl in the second row, but the huge price wasn’t made at the 2012 Madoura sale. While a copy of Ramié 605 did soar in that sale above its 3000 – 5000 British Pound estimate to achieve 10,625 pounds ($16,554), which was in fact a record high for the ceramic, that price was bested at the Sotheby’s London 2013 sale by almost 400%.

At Sotheby’s 2013 sale several other Picasso ceramics achieved prices higher than pieces from the same editions had at Christie’s historic Madoura sale the previous year. Perhaps the reason was that Sotheby’s, taking a cue from its competitor, had started to specifically target Chinese and Russian buyers. These collectors were already spending big money at the evening sales of Picasso paintings and drawings, the estimates of most of which started at over a million bucks. It was — for them — a new notion that they could pick up Picassos for less than $100,000. So you paid two or three times the estimates – the auction houses often kept estimates low just to get the action going. What bargains!

Of course when you are dealing with a lot of clever people all of whom are trying to outsmart one another reversals aren’t uncommon. There’s probably even Chinese and Russian words equivalent to the one we use in English when there’s a second reversal after the first: the double cross. Lately it’s come to light that some Chinese buyers haven’t paid for items they’ve won at auction. So perhaps once the buyer had a chance to consider things, the record price was something that existed only on paper (and in auction records), not in fact. And maybe underbidders researched the market a bit more thoroughly after the $75,590 record. Six copies of Ramié 605 have traded at auction since 2013 at prices ranging from $15,000 – 20,000 (Ramié 604, 606 and 607 have performed similarly).

Every sale is different, and when you are dealing with thinly traded items anything is possible. You only need two bidders to make an auction. If they both have a lot of money and perhaps not enough information then the sky’s the limit. The owl below, one from an edition of 300, just sold (18 March 2015) at Sotheby’s in London for 37,500 pounds ($55,343) against an estimate of about $4,400 – 7,300. At the same sale four other versions of owls of this shape sold for between $13,000 and $24,000.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

There’s one more wrinkle to this story. After the $75,590 record, knowledgeable collectors who had copies of Ramié 605 (or Ramié 604, 606 and 607) decided that their ceramics, too, were suddenly worth $75,000. Not surprisingly they haven’t been overanxious to consign the pieces to auction where they are still estimated $6,000 – $8,000, and it’s hard to find a dealer with one of these pieces whose asking price starts at lower than $75,000. Thus while demand remains strong the supply actually available for sale is far less than the real supply. Just a few birds fly out periodically, which may be why they still bring Madoura Sale prices.

But if everyone gets nervous that the market won’t sustain these prices and a few dozen or hundred (or thousand) owls were to fly out at the same time, look out below.

Value Mysteries: Picasso’s Runaway Bull Returns

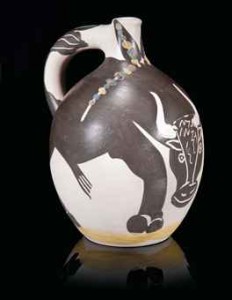

In my previous post I discussed the Case of the Picasso Ceramic Bull, “Taureau” as he is called in Alain Ramié’s definitive ““Picasso – Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works, 1947 – 1971.” Alain Ramié is the son of the Georges and Suzanne Ramié who created Picasso’s edition ceramics at the Madoura pottery.

The first of these Taureaus (AR 255 as it is identified in the catalogue raisonne) to sell at auction brought $87,000 in 1990. For the next two decades, however, at least eighteen other bulls from the edition of 100 sold (or were passed) at auction for prices averaging in the $20,000s. As late as April 2010 one sold at Christie’s in New York for $27,500. In October that same year another brought $25,000 at Sotheby’s New York. But something very strange happened at the next sale of AR 255, which took place at Christie’s South Kensington on June 25, 2012. The price was 97,250 British pounds — $151,263!

The first of these Taureaus (AR 255 as it is identified in the catalogue raisonne) to sell at auction brought $87,000 in 1990. For the next two decades, however, at least eighteen other bulls from the edition of 100 sold (or were passed) at auction for prices averaging in the $20,000s. As late as April 2010 one sold at Christie’s in New York for $27,500. In October that same year another brought $25,000 at Sotheby’s New York. But something very strange happened at the next sale of AR 255, which took place at Christie’s South Kensington on June 25, 2012. The price was 97,250 British pounds — $151,263!

What the hell happened in the intervening year and half that drove the price of Picasso’s ceramic Taureau up 500%?

To answer that question it is helpful to go back to last post where I discussed the factors that drove the price of the first Bull into record territory:

“Market inefficiency drives price volatility and, as with many markets, there are three factors that create inefficiency for Picasso ceramics: lack of knowledge, thin trading and what some people might call manipulation but which in reality is simply the interaction of small groups of people who think they are smarter than everyone else seeking to make money by exploiting the first two factors.”

Did any of these three factors exist after twenty years of stable prices for this ceramic? You’d think all the angles had been covered by now, and everybody knew all there was to be known, wouldn’t you?

Did any of these three factors exist after twenty years of stable prices for this ceramic? You’d think all the angles had been covered by now, and everybody knew all there was to be known, wouldn’t you?

But in fact all of these conditions still existed on June 25, 2012 when “The Madoura Collection” went up for sale in South Kensington. Parsing the facts, however, is difficult because in the art market — as in quantum physics — the facts change depending on how they are observed and by whom.

Let’s not call it manipulation because Christie’s in fact was smarter than everyone else when they packaged hundreds of ceramics that had been consigned by Alain Ramié into a hugely publicized, once-in-a-lifetime, sale-of-the-century type affair on June 25, 2012.

Looking like it had been made yesterday, this Grand Vase was the Madoura Sale’s top lot, selling for the equivalent of $1,146,143

Christie’s sale rooms in South Kensington were a perfect venue — one of the priciest neighborhoods in the world and the kind of place where the street traffic is comprised of billionaires. Right there in the window were scads of these charming, wacky Picasso pots and plates, which probably a lot of billionaires and their sisters and their cousins and their aunts had never seen before. These are the sort of folks who usually only bother with the big evening sales where even “restaurant Picassos” start at a couple million bucks. (“You know, Restaurant Picassos,” as Steve Wynn once educated me. “They’re not good enough for my museum so I put them in the restaurant.”) Here was an opportunity to pick up a genuine Picasso with the best provenance imaginable in such pristine condition that it looked like it had been made yesterday for estimates that began at a mere 1,000 pounds or even less. Stocking stuffers!

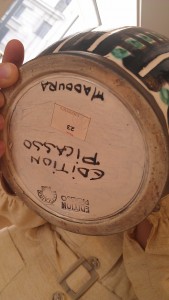

People who attended the previews reported that these were the archive copies of the Madoura pottery, the “bon à tirer” pieces, the very prototypes approved by Picasso so that editions could be recreated and sold inexpensively (originally) to the tourists. Strangely the Christie’s catalogue itself did not mention any of this, other than to identify the sale as “the Madoura Collection” and specify the edition size. In other words you might have bought the story but as in any auction you weren’t buying actual documentation beyond what was printed in the lot description.  Many of the ceramics were marked “Exemplaire Editeur,” which led to a lot of grumbling among cynics and old-time dealers who had been buying ceramics directly from Madoura — in some cases since the 1960s — and had never heard of anything marked “Exemplaire Editeur.” Nothing about Exemplaire Editeurs had been mentioned in the catalogue raisonne. How many of these things were there and when were they really made?

Many of the ceramics were marked “Exemplaire Editeur,” which led to a lot of grumbling among cynics and old-time dealers who had been buying ceramics directly from Madoura — in some cases since the 1960s — and had never heard of anything marked “Exemplaire Editeur.” Nothing about Exemplaire Editeurs had been mentioned in the catalogue raisonne. How many of these things were there and when were they really made?

The same people also complained that the person who Christie’s (and Sotheby’s) trusted to judge the authenticity of Picasso ceramics was the same person who consigned the pieces, a rather serious conflict of interest! No matter. It wasn’t the cynics who were going to buy at the Madoura sale, any more than they would have shelled out a thousand dollars for a $50 cookie jar at the Andy Warhol Estate sale or God only knows how much for Jackie Kennedy’s dental floss. The once-in-a-lifetime Madoura sale was geared toward once-in-a-lifetime buyers — this was their last chance to buy directly from the source. And buy they did. The two-day Madoura Collection sale was a huge success, taking in over £8,000,000 ($12,500,000), four times its total presale estimate, and was 100 percent sold by lot and by value.

It is interesting to note that not all of the ceramics in the Madoura sale were Exemplaires Editeur. Some were ordinary numbered and unnumbered production pieces. Others bore strange numbering like 113/157/200. A “Grand Vase” that sold for £265,250 was marked H.C 1/3. H.C. is an abbreviation for Hors Commerce, which basically meant not for sale. There is no mention of H.C. Picasso ceramics in the catalogue raisonne. These ceramics skyrocketed past their estimates like everything else.

When the purchasers go to sell their copies, will the market reward them for coming from the historic Madoura Sale (presuming the buyers have kept their receipts)? Or will they find their ceramics valued just like all the hundreds of identical others in the editions?

When the purchasers go to sell their copies, will the market reward them for coming from the historic Madoura Sale (presuming the buyers have kept their receipts)? Or will they find their ceramics valued just like all the hundreds of identical others in the editions?

And what about Taureau, AR 255, Picasso’s Bull that ran away in value? Will it continue to bring a huge premium over its bovine brethren?

In fact a year later the price of Taureau was down by more than half, an example from the edition selling at Christie’s New York for $68,750. A few months later Christie’s South Kensington did better, getting the equivalent of over $91,000 for one (rumor has it that they specifically targeted Chinese internet buyers who had no idea that genuine Picassos could be had so cheap). Not bad, but of course not in the same league as that Exemplaire Editeur Taureau that garnered $151,263 at the Madoura sale. How much, I wonder, is that once-in-a-lifetime ceramic worth today?

In fact, buried at the bottom of the definitions and abbreviations page of Alain Ramié’s catalogue raisonne is the note that there are three “publisher’s copies” for each piece. So perhaps there will be two more “once-in-a-lifetime” Madoura sales in the future. But an Exemplaire Editeur Taureau may not be in both: I appraised one purchased directly from Madoura in 2005.

Appraisals, Relativity and Value

Albert Einstein’s Relativity Theory changed the paradigm by which we view the world. Before Einstein people believed in absolute value. After Einstein nothing had an absolute value except the speed of light. If theoretical spaceships had to shrink and time itself had to slow down to make the equations work out, then so be it. Everything was relative. And then quantum theory threw another curve ball by revealing that everything was in the eye of the beholder. Just by looking at something you changed it.

Many people think that appraisals of objects somehow get around Einstein, quantum physics, the Uncertainty Principle and the whole works. They like to think that at least as of the date of the appraisal report, an appraiser can record the absolute value of an object. Unfortunately this is not true. There is no absolute value of a work of art or piece of antique furniture or even money itself, which fluctuates in relation to other currencies, other stores of value and how you measure it.

Take gold for instance. The largest gold coin in the world was produced by the Perth Mint in Australia — one metric tonne of gold, which equals 35,274 ounces. You can find a lot of references to this artifact on the internet and calculations of its “value” (for instance gold at $1300 per ounce makes this coin “worth” more than $45,000,000 US dollars). Presumably the Perth mint will tell you what they want for it if you contact them directly, but I’d be surprised if they’d take the daily bullion cost. This big chunk of change must have cost a lot to produce; there’s bound to be a premium. How much is only one question. Another might be what’s the tab to get it from Perth, Australia, to your apartment in Brooklyn? How about the cost of a new security system? What does it cost to shore up the floor?

Whatever the premium is for a one tonne gold coin I’ll bet it wouldn’t come anywhere close to the premium on this little baby to the right. Not the big one — the little fella. This item is what numismatists call a California Gold Token, which was never even legal tender. It also has a hole in it, which usually kills a coin’s value for collectors.

Not the big one — the little fella. This item is what numismatists call a California Gold Token, which was never even legal tender. It also has a hole in it, which usually kills a coin’s value for collectors.

The last time I found a California Gold Token with the Moon and Shooting Star, similarly holed, for sale the price was $799.99. Tokens like these are as thin as a parking ticket and weigh typically about one gram — .035 oz. Most were only 10 karat gold to boot. Even a non-mathematician can see that this bad boy is worth quite a bit more than its weight in gold. By at least one measure (premium above the bullion value of its gold) it is worth astronomically more than the one tonne coin.

But there doesn’t seem to be one of these for sale anywhere in the world right now, so even if you had $45,000,000 you can’t buy it. It’s literally priceless. And even on the day that it was priced at $799.99, its value was relative — worth about a minute’s worth of work for the highest paid CEO in America, Elon Musk, or almost two years’ annual income for the average household in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Now imagine if Jeff Koons made a ten foot high version of this California token in mirror-polished stainless steel. I don’t know what it would be “worth,” but at Sotheby’s or Christie’s it would probably bring a higher price than the solid gold version. At least this year.

What is an Appraisal and Who Needs It?

When people have a piece of art they want to sell they often think that their first step should be to get an “appraisal” so they won’t be taken advantage of.

But what is an appraisal? When your friend who owns an antique shop says, “This is worth about three thousand bucks,” is that an appraisal? How about when an imperious looking chap wearing a bespoke suit and a British accent looks at your painting on THE ANTIQUES ROADSHOW and declares that it would bring $40,000 – $50,000 at auction? Did you get an appraisal?

The dictionary might say both of these are examples of appraisals, but according to the Appraisal Foundation which was authorized by Congress as the source of appraisal standards and appraiser qualifications, to be credible an appraisal must conform to rules that the Appraisal Foundation refines and publishes every two years in a big fat book entitled the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP). USPAP compliant appraisal reports can run dozens of pages even for single paintings in order to conform to the standards. To jump through the required hoops takes a lot of hours on the part of the appraiser, so USPAP compliant appraisals are expensive propositions. USPAP says that even oral appraisals must conform to all the myriad standards and be documented in a work file, so it is unlikely that any oral appraisal is USPAP compliant. Members of the professional appraisal associations (the Appraisers Association of America, the American Society of Appraisers and the International Society of Appraisers) all REQUIRE their members to perform only USPAP compliant appraisals.

A person needs a pet grooming license in New York City to shampoo your poodle. To come into your house and do an “appraisal” of your silverware, he doesn’t even need a business card that identifies him as an appraiser. Anybody can give you an “appraisal.” For that matter anyone can issue a “Certificate of Authenticity” for your Picasso, which will be just as credible as the issuing party. The whole point of USPAP and appraisal organizations is to make sure that the public can have confidence in appraisals done by unbiased professionals experienced in the business of valuation – not the business of grooming poodles or selling your property to make themselves a profit.

Bottom line, a credible appraisal is usually a lengthy document conforming to USPAP standards written by a member of a professional appraisal group. If you’re dealing with the IRS for a charitable contribution or for estate tax purposes, chances are you need such a document. Your insurance company may also require it to protect your expensive art collection. Perhaps a credible appraisal is necessary in a court situation — a divorce or a lawsuit.

But if you just want to get some idea of what your art is worth so you can sell it, you very well may not need and probably shouldn’t have to pay for a professional, USPAP compliant appraisal report. So ask your dealer friend for his opinion, run it past an auction house if you like, but be aware that the oral “appraisal” you receive may not be worth the paper it’s written on.

What makes something valuable?

What makes something valuable?

A long line of discussion usually follows, but at the end it becomes clear that what makes something valuable is the same thing that makes the universe visible: a self-aware mind that can perceive it.

When a tree falls in a forest and there is nobody there to hear it, does it make a sound? Many people in our 21st century materialistic culture will say, yes, it does. But if these people didn’t exist — indeed if no people at all existed, no conscious entities anywhere in our universe, would the universe exist?

Our universe is limited to our perceptions. Flies have a much different view of reality than we do, and in that sense at least they are creating their own reality. But quantum physics indicates that what we perceive as a chair or a cloud or a block of gold are all in fact particles or maybe vibrating strings winking in and out of existence. If we weren’t here, then in a very real sense our universe would not be here either.

Value is the same thing in a parallel way. If we decide that gold is valuable, then it is. If we decide it is worth $200o per ounce that is what it is worth (at least in dollars) though it is exactly the same thing that was worth $500 per ounce a few years ago. The hyper-inflated currency of Weimar Germany was worthless because the German people perceived that it was backed by nothing. When Germany replaced the worthless Papiermarks with new Retenmarks, which it was announced were backed by the sacred soil of Germany, suddenly people perceived that the new currency had value. However, no one was able to take the paper bills to a bank and exchange it for a wheelbarrow of German dirt.

It is the perception, the thought that creates value. This website is about thought.

Appraising Damaged Fine Art Ceramics

Picasso, Chagall, Miro, Leger, Matisse and other important 20th century artists created ceramic works. It could be a serious mistake for appraisers to use the same percentages to assess loss of value to such fine art pieces as some have suggested for damaged decorative art ceramics and porcelain.

Picasso personally decorated over 4,000 ceramics at the Madoura pottery in the town of Vallauris in the South of France from 1947 to 1972. Most never entered the market. However, editions after 633 of Picasso’s designs were recreated by the artisans at Madoura under the artist’s supervision. These “Edition Picasso” ceramics were at first sold inexpensively to tourists, but such pieces became highly collectible over the years. Edition sizes were anywhere from 25 to 500, bringing the total production to almost 120,000 pieces.

It is thus not uncommon for a personal property appraiser to find Edition Picasso ceramics in an otherwise modest home or estate. Such ceramics, which might have been purchased for less than a hundred dollars in the 1950s or 1960s, can be worth tens of thousands today. Large pieces, which are much rarer than the plates, fish, owls and ashtrays that most tourists brought home, can sell in six figures.

The Jane Kahan Gallery has been dealing in fine art ceramics, especially Edition Picasso pieces, since 1973. We have found that this is not a market that focuses on condition. You do not see Dr. No-type collectors at auctions with black lights and fluoroscopes. Repairs and restorations – as long as they are undetectable to the unaided eye – are rarely discussed in galleries or auction houses, though presumably condition reports would be available if requested. Condition is simply not relevant in the same way it might be with stamps or color field paintings or prints where it is of prime importance. If a piece looks damaged or fiddled with, it’s difficult to sell, either at auction or in galleries. If a ceramic looks perfect, however, then professional buyers (who constitute most of the auction market clientele) treat it as good regardless of what may lurk beneath the surface.

In this litigious society appraisers must therefore be careful with their own opinions, biases and assumptions about condition issues as they relate to fine art ceramics. Regardless of how much an appraiser may believe that condition should affect value, each market has its own realities, which no value formula or guidelines can repeal.

In this litigious society appraisers must therefore be careful with their own opinions, biases and assumptions about condition issues as they relate to fine art ceramics. Regardless of how much an appraiser may believe that condition should affect value, each market has its own realities, which no value formula or guidelines can repeal.

The fact is that perfection was not something that Picasso, nor many other artists, cared about. Picasso cared about the art, he didn’t care about the artifact – a distinction that appraisers reverse to their peril. Picasso never permitted any of his ceramics to be discarded, no matter what their condition issues. There was even a special “mechanic” at Madoura to whom he entrusted the repairs of items that had had firing accidents. We have had at our gallery such a piece, with staples on the back to hold a crack together. This ceramic is pictured in a 1948 magazine with the crack clearly visible. An appraiser inexperienced in the market for fine art ceramics might think this plate is less valuable than a “perfect” piece. Picasso did not think so, nor do many collectors. Nor do we (though we might if it weren’t as attractive and desirable a subject).

In 1951 Chagall created a dinner service as a wedding gift for his daughter. The family used this service at table. Like Picasso’s ceramics, these plates, saucers, cups and platters were soft earthenware. They chipped. A few such pieces entered the marketplace. The chips are as identifiable as fingerprints and make for a compelling provenance. Do they lessen value? We don’t think so. Repairing such damage might even be seen as compromising its integrity.

An appraiser might assume that condition is more important with Edition Picasso ceramics because they were made in quantities, like prints. This is not necessarily the case. However, when an expensive vase falls off the shelf during an earthquake and shatters into pieces, few would argue that there has been a loss. Assessing this loss can present major challenges and traps for appraisers, especially those inexperienced in this sophisticated market.

Consider this parable into which I have incorporated some auction sales and condition issues of a real Edition Picasso ceramic.

Late in 2003, Helene, a fictitious St. Louis appraiser, is called in by a Dr. No (not the same Dr. No who is so scrupulous about condition) to evaluate a large Edition Picasso ceramic vase that accidentally has been broken into pieces. Rather than waiting until the ceramic is repaired and then consulting with experts in this market to determine its post-restoration value, Helene applies percentages suggested in an industry handbook for catastrophic damage to “modern ceramics.” She declares in her loss/damage appraisal that the vase is a total loss, value zero.

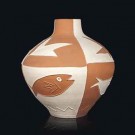

The ceramic in question is Oiseaux et poissons, a large and relatively rare vase, number 291 in Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonne of the Edition Picasso ceramics. A vase from the same edition of 25 had sold at Christie’s London in October of 2002 for $46,590, so Helene puts down this number as the amount of the loss. (The ceramic would probably have been $65,000 or more in a gallery, but Dr. No didn’t have replacement value insurance.)

The ceramic in question is Oiseaux et poissons, a large and relatively rare vase, number 291 in Alain Ramié’s definitive catalogue raisonne of the Edition Picasso ceramics. A vase from the same edition of 25 had sold at Christie’s London in October of 2002 for $46,590, so Helene puts down this number as the amount of the loss. (The ceramic would probably have been $65,000 or more in a gallery, but Dr. No didn’t have replacement value insurance.)

The insurance company takes possession of the shards and has the vase skillfully restored. It then sends it to Sotheby’s in New York, where it goes into a April 2004 sale and sells for $30,000. Already one can see that, by any definition, the “value” of the ceramic is significantly more than zero. In fact Sotheby’s gave it a presale estimate of $40,000 to $60,000, so it is clear that Sotheby’s didn’t seem to care overly that the piece has been repaired (though the words “skillfully restored throughout” are placed into the catalogue entry).

The buyer promptly sends the ceramic to Christie’s London, where it is estimated at ₤20,000 to 30,000 (roughly equivalent to the $40,000 to 60,000 Sotheby’s estimate) and made the cover lot for an October 2004 sale. This time no off-putting mention of restoration is made in the catalogue, but the ceramic does not sell. Note that when Sotheby’s mentioned condition in the catalogue, the piece sold. This time no mention was made, and the piece did not sell.

Condition information is not generally recorded in on-line databases, so potential buyers looking up the auction records for this ceramic wouldn’t have known about the condition of the piece unless they asked for a report from Christies. Few professional buyers of Picasso ceramics are concerned enough to do this, as I have said before. Someone checking the auction databases, however, would have noticed that the last sale of this ceramic was for $30,000, so perhaps the estimate might just have seemed too high for savvy buyers.

In any case Christie’s puts the piece in the April 2005 auction and lowers the estimate to ₤15,000 to 20,000. This seems to do the trick, because the totally restored ceramic sells for ₤31,200 (then $58,646.) to a French dealer, Monsieur Yes (whom I have made up entirely out of whole cloth, as I have the rest of this story, except for the auction

records for this ceramic and its condition issues, which are real). Monsieur Yes has decades of experience with Picasso ceramics. Condition problems are irrelevant to him unless there is a visible problem, which is not the case here (and if there were a visible problem, he would have it repaired). He takes the ceramic back to Paris and subsequently sells it to an American tourist for the equivalent of $125,000 (they get very good retail prices in Paris). He does not disclose that there is restoration because, not having asked for a condition report, he does not know. And even if he did know, in his experience this is not relevant to the value of the ceramic.

The buyer, Mrs. Maybe, proudly ships her prize back home to St. Louis, and early in 2006 she engages Helene the Appraiser to assess the replacement value of her belongings for insurance purposes. Edition Picasso ceramics are numbered, and Helene cannot help but notice that the number of Mrs. Maybe’s Oiseaux et poissons is the same as Dr. No’s. It is the same ceramic.

What dollar value should Helene assign in her appraisal? Two years ago Helene herself had declared this piece worthless. Its fair market auction value of record is $58,646 from the Christie’s sale. Its retail replacement value is the $125,000 for which Mrs. Maybe recently purchased it in Paris – in fact another vase of this type probably could not be found at that point for any price. Similar to Schroedinger’s Cat from quantum physics which found itself in the peculiar position of being both alive and dead at the same time, Mrs. Maybe’s ceramic appears to be simultaneously both worthless and overpriced.

Helene feels ethically bound to disclose the issue of condition of this vase to Mrs. Maybe, but she should think very carefully before she does so. Monsieur Yes does art fairs in New York, Los Angeles and Miami, and he can’t afford to have integrity impugned. He may very well sue if Helene tells Mrs. Maybe that he has sold her a worthless vase for $125,000.

Good luck with your appraisal, Helene.

Copyright @ by Charles Mathes