Art Consultants and the Agency Problem

When I was Director of a New York City gallery people often came in, saw an artwork they liked and then sent someone whom they called “my friend,” or “my dealer,” “my adviser,” or “my expert” to look over the piece and negotiate for them. Today more and more collectors are buying art through this kind of of representative. In fact there’s a whole profession of people calling themselves “art consultants.” I’m now one of them.

Such representatives theoretically are a great thing for collectors. There’s a widespread perception that dealers are used-car-salesmen-type hucksters eager to take advantage of honest folks. Sadly this perception is sometimes true. Many dealers will tell you that whatever they happen to have in their gallery is absolutely the best thing you can possibly buy and the price is a fantastic bargain. They’ll routinely badmouth anything you may like from their competitors out of sour grapes or just for sport, unless they can somehow cut themselves in.

So what could be wrong with getting an experienced professional to help you make sure you’re getting a good piece of art at the best price?

Well, what’s wrong is a well-known business dilemma called the Agency Problem, which Investopedia defines as follows: “A conflict of interest inherent in any relationship where one party is expected to act in another’s best interests. The problem is that the agent who is supposed to make the decisions that would best serve the principal is naturally motivated by self-interest, and the agent’s own best interests may differ from the principal’s best interests.”

Thus at my old gallery the first thing out of the mouths of some clients’ “friends” was sometimes: “So what’s my cut?” or words to that effect.

When faced with a choice among several works that the client liked, a lot of “friends”made their recommendation based on the highest rebate to them, or kickback, or whatever you want to call it. Dealers like to call it a “commission.” Such commissions are so common that many people in the art world think of them as simply the way business is done. Not everyone necessarily agrees, including a judge in the U.K. who recently ruled against a dealer who sold a painting for a million dollars more than it was consigned for and then pocketed the difference as his commission (this case and others are related in an eye-opening article by Adil Essajee entitled “Commissions – the best kept secret?”).

When faced with a choice among several works that the client liked, a lot of “friends”made their recommendation based on the highest rebate to them, or kickback, or whatever you want to call it. Dealers like to call it a “commission.” Such commissions are so common that many people in the art world think of them as simply the way business is done. Not everyone necessarily agrees, including a judge in the U.K. who recently ruled against a dealer who sold a painting for a million dollars more than it was consigned for and then pocketed the difference as his commission (this case and others are related in an eye-opening article by Adil Essajee entitled “Commissions – the best kept secret?”).

To avoid these kinds of conflicts of interest, many art consultants charge on a fee basis or by some complex percentage arrangement. However, this often requires fat legal contracts specifying every possible contingency and can still result in misunderstandings. Consultant A might need only a single conversation to stop a client from making a million dollar mistake and instead show him how to double his investment while giving him years of pleasure. But he’ll end up with a few hundred dollars if he charges by the hour, as opposed to Consultant B who stands to make a hundred thousand by taking a 10% commission on the million dollar mistake. And Consultant C, who charges a commission to both the buyer and the seller for putting deals together (hey, it works for Sotheby’s and Christie’s…), will end up being the most successful consultant in town — or at least the richest.

If it sounds like some art consultants may just be dealers dressed in sheep’s clothing, it’s probably because it’s true — though there certainly many consultants who are e xactly what you would want them to be — honest, experienced professionals who want to help you navigate treacherous waters. And to make a living through their knowledge and love of art.

xactly what you would want them to be — honest, experienced professionals who want to help you navigate treacherous waters. And to make a living through their knowledge and love of art.

It’s helpful to remember that there are only two parties really necessary to the sale of art: a seller and a buyer. Everyone else — dealers, auction houses, consultants and friends (or whatever you want to call them) — are middlemen subject to the Agency Problem, some more than others. So if you’re a person who wants to buy or sell art, how do you get around these people?

The answer is that you usually can’t — unless you want to start a gallery or auction house of your own. And this is the wrong question to be asking anyway. The right question is: how can we both get what we want by working together? The answer will involve communication, transparency, trust, realism, mutual respect and a sincere desire on the part of both parties to look out for one another’s interests, not just your own.

Art as a Form of Money

Money today isn’t what it used to be.

In previous centuries the standard medium of exchange was gold or other precious metals. These commodities had certain attributes that made them ideal: they were rare in nature and hard to refine, thus limiting their supply. They were also physically handsome to look at and could be fashioned into beautiful things. They were easier to carry around than more primitive stores of value, such as cows and wives.

Back then if you wanted a piece of paper to be perceived to have value it had to be exchangeable for the physical commodity it represented. Today the value of “fiat” currencies — i.e., money that is based on governments declaring it to be money rather than making it exchangeable for commodities — is taken for granted. A new twist is that if enough people agree that something is money (like Bitcoins), then it becomes money — though the rate at which such things can be exchanged for goods and services can be wildly erratic.

Which leads us to Art. A few hundred years ago anybody could glance at a painting by Leonard da Vinci or Raphael and know that it was art. In the old days art was like pornography; maybe people couldn’t define it but they knew it when they saw it. Today, nobody knows it when they see it. Art no longer has to be beautiful or require a lot of skill to produce like it used to. Part of the reason that the Impressionists were initially ridiculed was the perception among older artists who had labored for decades perfecting their craft that any idiot could dab some paint on a canvas and create this “new” stuff. But all that has changed now.

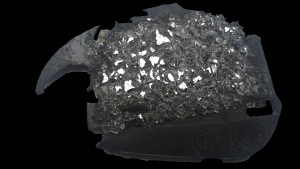

Take a look at this work:

Let’s say I’m an artist, and I say this is art. Is it? Or suppose I am an art critic. I, too, say it is art. Is it? Or I am an art dealer who agrees that this is art. Is it?

While all of these folks are influential in determining what art is, I submit that none of their opinions ultimately matter unless the item can be exchanged for money. Perhaps I am making a distinction between “art” and “the value of art” but if something has no value, wouldn’t it be more correct just to call it “trash”? What’s the point of a word if nobody knows what it means? In our culture art means money.

Consider three virtually identical 30 x 30″ canvases, all covered with red paint. The first was done by a professional house painter, who did it to give you an idea of the color he can paint your bathroom. He won’t charge you for it if he gets the job, otherwise he’ll bill you for the cost of the materials. The second was produced in a factory by an industrial robot — it is on sale at Walmart for $49.99. The third was painted by a “name” artist whose work has been exhibited in numerous important galleries over decades. It is identified in the Sotheby’s catalogue as a masterpiece and estimated at $360,000 – $400,000. Isn’t the one at Sotheby’s the only one that’s “art?” And if there were a fourth identical red canvas, but one done by a young artist on sale at a local frame shop for $1000, most people would probably say that though it might be art it’s not as good as the one at Sotheby’s. In our culture the price of something pretty much determines its quality, not the other way around.

Now forget about semantics, and about philosophical questions like “What is Art?” Take a look at the two items below. One is a form of money and one is a form of trash. Can you tell which one is which?

It doesn’t matter what your level of taste or education is, there’s no real way to determine which one is garbage. But what if I told you that “Mirrored Armadillo” was exhibited by the Gagosian Gallery? And “Woody Memories” is in fact a natural item — the scalp of a woodpecker.

However, you still may be jumping to the wrong conclusion.

“Mirrored Armadillo” was exhibited (i.e. displayed publicly) by (i.e. in proximity to) the Gagosian Gallery. I found it in the street about a block up from Larry’s Madison Avenue place. I believe it is a side mirror that was knocked off a car and run over a few times. Woodpecker scalps on the other hand were used as money by the Karok people of the Klamath River region, in northernmost California and adjacent parts of Oregon. The example above comes from the collection of the American Numismatic Society.

Either one plus $2.50 will buy you a cup of coffee in New York City.

And what about contemporary artist Tracey Emin’s bed?  If you aren’t already familiar with this, you might not consider it Art-with-a-capital-A, what with the used condoms, empty bottles of vodka, dirty laundry and the like. But the Tate Gallery in London exhibited it in 1999 and it was shortlisted for the prestigious Turner Prize, causing great indignation among the hoi polloi who thought it was garbage. Whether it is art or not was settled by Charles Saatchi who bought it for £150,000. But is it good art? This question was settled the way we in our culture now settle such matters — namely at auction. It brought £2.2 million at Christie’s this past June.

If you aren’t already familiar with this, you might not consider it Art-with-a-capital-A, what with the used condoms, empty bottles of vodka, dirty laundry and the like. But the Tate Gallery in London exhibited it in 1999 and it was shortlisted for the prestigious Turner Prize, causing great indignation among the hoi polloi who thought it was garbage. Whether it is art or not was settled by Charles Saatchi who bought it for £150,000. But is it good art? This question was settled the way we in our culture now settle such matters — namely at auction. It brought £2.2 million at Christie’s this past June.

As for “City Within the City,” it looks as much like art as anything else. If I could make a hundred somewhat like it each year and get an important dealer to show them at Art Basel, put a few pieces at auction and bid up the prices (rather illegal, of course, but do you really think it isn’t being done?), then I will have created some real value. But I’m just interested in art and was happy to have seen it when it was exhibited on 57th Street.

The emperor may not be wearing clothes, but they look like a million bucks!

Stephen Hawking Is Not So Smart

The physicist Stephen Hawking said in a famous quote, “I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.”

I find this an extremely odd statement, especially from a scientist. It completely ignores what powers the computer, namely electricity. Yes, collections of computer components will not go to heaven. But if a computer dies, does electricity cease to exist?

Whatever “life” is, it has more in comm0n with electricity than with circuitry. When the human body is no longer animated by life, a person dies as surely as the computer on which someone has cut the power. But electricity still exists even when the computer breaks down. When a person dies, isn’t it only logical that life still exists?

Maybe the fairy story is that we are just a collection of organic components.

Mathes Missive From Moscow #1 – The Cast of Characters

Greetings, Fellow Traveler,

As you may know, my gallery is exhibiting this year for the first time at the Moscow World Fine Art Fair.

Such an endeavor might sound exciting to you. Quarterbacking for New York Giants probably sounds exciting to a lot of people. But if you’re the one who is holding the football as a bunch of guys the size of refrigerators charge toward you at full speed, different emotions may well up. The folks who ride in metal boxes atop rockets into outer space, or play leads in Broadway shows, or make billion dollar bets on oil futures probably feel more scared shitless than excited, too.

Being a writer, I like to think that I can get some perspective and process certain unpleasant emotions by putting things down on paper. It may not actually help, but it gives me the illusion of doing something constructive. And at least there will be a record of what happened in case I am never seen again. I am more scared right now than excited  for reasons that will never become fully apparent. As an art dealer I have to keep everything confidential. The art business runs on secrecy. I’ll discuss this in more detail later (but unfortunately I will not be able to tell you the actual details).

for reasons that will never become fully apparent. As an art dealer I have to keep everything confidential. The art business runs on secrecy. I’ll discuss this in more detail later (but unfortunately I will not be able to tell you the actual details).

Perhaps you have noticed by now a certain sentence structure polish and lack of hysteria that doesn’t quite jibe with the juicy terrors I have been implying are in store. This is because I am composing this ahead of time in New York and plan to send it before we leave on the afternoon of Monday, May 19th, 2008. We will arrive in Moscow at 10:00 a.m. on Tuesday (Moscow is 8 hours ahead of the Eastern U.S.) The Special Invitational Charity Preview to the opening night Gala Opening Night takes place on Monday, May 26 (we are invited, but we would have to buy a table for 10,000 Euros if we wanted to come to the sit down dinner with Mme Medvedev), so we have a week to explore Moscow and set up our booth before the oligarchs descend upon us with their billions. The fair closes on Monday, June 2nd.

Who exactly is the “we” to which I am referring? Allow me to introduce the cast of characters. There are three of us, not including a special cameo guest appearance, which will be revealed in Moscow. Me, you know. At least you thought you did until you wade a bit deeper into these narratives and discover the horrifying extent of my neuroses (you may also not be aware that I was once a member of the National Rifle Association).

The true heroine of this adventure is our fearless gallerist, Jane.

The true heroine of this adventure is our fearless gallerist, Jane.

Every business must have an engine, and Jane is ours (it was her inspiration to go to Moscow). She’s an explosion of creativity, exuberance, experience, daring, shrewdness, knowledge, vision and a perhaps just the teeniest bit of lunacy. The problem with explosions is that they tend to blow things up, which is where I come in. An explosion by itself isn’t necessarily the best thing to have around, but if you figure out how to put an internal combustion engine around it, you can drive to Schenectady. I try to figure out how we can channel some of Jane’s creatively exploding limitless energy. I must have succeeded a little bit since 1) the East Coast is not a smoldering ruin, and 2) we are about to invade Russia — a formidable exercise in logistics (but one that didn’t work out so well for either Napoleon or Hitler). And you wonder why I’m a little nervous?

In recent years Jane has found her true calling as a photographer of small living creatures. These are mostly dogs, but Jane has also stopped traffic to digitally capture cats, horses, donkeys, ducks, geese, pigeons, wolves and assorted others (even some humans). Hopefully, she will be bringing her camera to Russia.

But, how — you may ask — do we propose to sell artwork in a country where we don’t even speak the language? And who will protect us if we get into trouble? This leads us to the third member of our little team: Julia.

The lighting was a little low here in the Turkish restaurant where she was performing her belly dancing act that night, but you may still be able to tell that Julia is in very good physical shape. Besides being an expert in all manner of gypsy exotic dancing (don’t get any wrong ideas, those are knives in her hands),  Julia is also a personal trainer. Jane signed up with her at the JCC and Julia was such a good personal trainer that it nearly killed her. Julia is also a world-class simultaneous translator (she was born in Ryazan, Russia and went to University in Moscow, majoring in English which she now speaks fluently). If her passion weren’t dance, she would probably be a supreme court justice or a nuclear physicist — she’s that smart (though she eats like a bird). Julia will be coming to Moscow as our assistant, translator and tour guide. (She actually looks much less menacing without her mask and knives, which presumably she will not attempt to bring in her carry-on bag; you will have to wait for the next Missive to see her unmasked.)

Julia is also a personal trainer. Jane signed up with her at the JCC and Julia was such a good personal trainer that it nearly killed her. Julia is also a world-class simultaneous translator (she was born in Ryazan, Russia and went to University in Moscow, majoring in English which she now speaks fluently). If her passion weren’t dance, she would probably be a supreme court justice or a nuclear physicist — she’s that smart (though she eats like a bird). Julia will be coming to Moscow as our assistant, translator and tour guide. (She actually looks much less menacing without her mask and knives, which presumably she will not attempt to bring in her carry-on bag; you will have to wait for the next Missive to see her unmasked.)

So, thank you very much for listening, and this ends our introduction. If you want to find out more about the art fair the way the organizers wish for it to be perceived, go to www.moscow-faf.com A more interesting story (and one with a happy ending, I hope) will take place here. Next stop – Russia.

Nostrovia!

Charles

Copyright © by Charles Mathes

My New York by Charles Mathes

I’m the author of a series of stand-alone mysteries, each featuring a different young woman with a problem in her past. A hotel-inspector orphan searching for her family. The professional magician desperate to understand why her grandfather was murdered. A pair of antique-dealer sisters whose grandmother sank into poverty after a Broadway career. A professional stage fight director whose father lies in a coma.

The books appear to be connected only by the word “Girl” in the title, but in fact each novel includes the same pivotal character with whom all of my heroines interact. The character’s name is New York City. Like any pivotal character my New York is a catalyst that forces my heroines to change, to grow, to develop.

Perhaps this is because New York forced me to change. Everyone who comes to the City to forge a career has to put aside old concepts of how things are supposed to work and reinvent him or herself to survive in a town that is both without limits and without mercy.

The stereotype is that you have to move fast here or you’ll get trampled, talk fast or you won’t get in a word edgewise and think fast or you’ll be left without the shirt on your back or a penny to your name.

The reality is that the city lets you be anything you want to be (which is probably why so many misfits end up here), but always makes you keep things in perspective. It’s hard to think you’re such a big deal when buildings soar sixty stories on every corner, but it’s hard not to feel like a king or queen when you’re walking down Fifth Avenue and the sun is shining and the city is pulsating with the energy of a million people certain that they are in the nexus of the world.

Like most “real” New Yorkers I was born out of town – Cleveland, Ohio, to be exact. My first taste of the Big Apple came on a family vacation when I was just a kid. I was used to the suburbs and had never seen anything like Manhattan before. Our hotel was something out of a movie, as bustling and gigantic as an airport, full of little shops and high ceilings and bellboys running around in red uniforms. A cab took us to a nondescript building on a seemingly deserted street. We opened the door and found ourselves in a cavernous restaurant full of beautifully dressed sophisticates. I ordered Lobster Thermador and nobody batted an eye.

When we came out of a movie theatre on Broadway at eleven o’clock at night the streets were more crowded with people than downtown Cleveland was at rush hour. And such people! Ladies with faces thick with make-up and cynicism smiling out from dark corners at passersby; guys with sharkskin suits and pug noses lighting up Parliaments with gold cigarette lighters; a leathery old broad dressed like a fireworks display and bellowing to herself about how the Commies had taken over the government.

My father, the traveling salesman, told me that if you waited around long enough in Times Square, you would eventually run into everyone you had ever met. I gave a skeptical glance around and to my astonishment was hailed by a kid I recognized from summer camp in Indiana the summer before. I was hooked. New York was pure magic, a place of miracles!

In high school I found myself in the City again, this time with my high school choir. Carefully chaperoned, my friends and I did the usual tourist things – saw the show at Radio City Music Hall, went to the top of the Empire State Building, checked out the U.N. Then we went up to Harlem and sang a concert in the chapel of the Salvation Army and saw a different New York City, a city where tourists never went but one that just as alive and full of heart as anything downtown. I felt welcome and safe and happy. New York was an old friend.

As a college freshman I came back to New York by myself. Confident that I would have another great time, I checked into a “reasonably priced” hotel in midtown. The room was tiny and dark. Sirens wailed in filthy streets far below. I walked through Times Square again, this time without my friends or my family. I didn’t recognize a soul. Thousands of people rushed by, none of them caring whether I lived or died. I ate alone in a greasy diner, the only place I could afford, and was hustled out when they wanted the table for a larger party. The city was overwhelming, gigantic and anonymous. I never had felt so lonely in my life.

After that I had no desire to go back. Each time I thought about New York, it grew bigger and uglier and more dangerous in mind. It was the seventies. Johnny Carson assured us that if we ventured into Central Park we would get killed. Kitty Genovese’s screams didn’t bother the neighbors. Every subway car pictured in the movies was a graffiti-scribbled horror. New York was a gigantic back alley that ate up idealistic young people and spit them out, where cops answered domestic disturbance calls and got shot in face. New York was Hell.

Yet every Sunday through all the time I was in college, I would sit in a restaurant in St. Louis or Pittsburgh and read the New York Times. I wanted to be in the arts, and there was no getting away from the fact that if I wanted a “real” career, I would one day have to come back to New York. That’s just the way the country is set up. New York is the focal point, the main stage, the major leagues. Sure you could have a nice career as a “local” artist or actor or writer or musician, but you would never be in the same category as those folks who had made it in New York.

It isn’t fair, of course, but it’s true. New York is like the sun. The other cities in America – and increasingly the world – are mere planets, trapped for better or for worse in New York’s gravity, illuminated by its brilliance. This I think is why people outside of New York tend to see the city, either in memory or in imagination, as some kind of huge monolithic menace. They speak of New York this, New York that – as if the city really were a character, as if it had a mind and objectives of its own.

It doesn’t of course. It’s just a bunch of concrete and glass, steel and asphalt, flesh and blood. Its very mass and complexity, however, has the power to turn grown people into children when they see it for the first time, which I think is reason why my heroines all end up here at some point – not just because gravity pulls everyone here eventually, but because when a person sees New York for the first time, he or she invariably sees it as a child, with a child’s terrible sense of magic and wonder and awe. That’s what changes them. That’s what makes them grow. Frankly it’s something I want to experience again and again, something I want to share.

Eventually, of course, I came here to live. I had to. I sold my car and cashed in my stamp collection and made arrangements to stay with a friend I knew from college. All my bridges were burned. As my plane landed with LaGuardia I knew I had enough money to hold out for three months. If I couldn’t get a job in that time, I didn’t know what would become of me. I was scared to death.

As the taxi carried me and the three suitcases which held everything I owned in the world over the Triborough Bridge, the towers of the city suddenly flashed into sight, twinkling with sunlight and the dreams of million young people like me. It was majestic and awesome and magical. Gershwin seemed to well up out of nowhere, just like in a Woody Allen move.

Suddenly all the fear, bad memories and awful anticipation were gone. I was a child again. I knew I was home.

(This essay originally appeared in Mystery Scene Magazine)